J.P Roberts

I found out today that John Roberts died. He left us last Thursday. Driving through Downtown Washington D.C. in the baking heat, I had just finished bartering a second-hand folding bike for my hand-restored boat. I know how to fix this broken bike. I had the confidence to learn how to fix the boat, too, and then teach myself navigation over five thouseand sea miles around the Carribbean. I am known as a technician. Generally, I’m sure I can learn. I am sure because of John.

John was my childhood friend. When the bullies were excluding me, when I wasn’t number one in class, John was there in his workshop next-door in the ‘Back Lane’ at home. He was more interested in why the clutch wouldn’t fit into the engine of the 1920s vintage car that the family still drove around. Why the TVO, needed to start his 1956 Fordson tractor, was so hard to mix these days, and which meccanno parts I needed for my latest child-engineering experiment. He was twenty years older than me, but remained, throughout my life, ageless. He and his dad, Uncle Phil, had a ‘train room’ in the top floor of their house filled with vintage toys, ‘00’ and ‘Tiple 0’ gauge model railways round the room, and masses of intricate antique meccano.

I was part of their family like I was part of my own. One of the earliest photos of my childhood has me standing in front of a big orange tractor wheel with a paintbrush in my hand, drippping orange onto the dust of the lane.

Later in life, John was to teach me to drive on that tractor, with its grinding gearbox and wrought-iron sprung seat. I was king of the world, and, at the ‘working weekends’ which John helped organise, run by the villagers and parish of Little Casterton, I was one of the only ones allowed to plough furrows alongside seasoned old-time Lincolnshire farmers, with their traction engines, cross-field cable reciprocating ploughs, and Massey and Internation lightweight harrow rigs.

In the barn the vicar would conduct an outdoor Harvest Festival service, and the W.I. (Womens Institute) would gather alongside the ladies and wives of the parish to serve tea, scones, and finest home-made Lincolnshire sausages, while the threshing machines belched and wobbled dust and steam outside, and the Spitfires and Lancasters flew overhead (Uncle Phil, ex-RAF engineer, had friends in (literally) high places, who would orchestrate a vintage fly-by for the event.)

There were roadmens’ sheds, towed at four miles an hour behind the traction engines, assembling from across the huge county of Lincolnshire and beyond, and Lister, Blackstones and Atkinson well-pumps, sometimes retreived as four-ton lumps of limescale from Collyweston slate pits underground Lovingly restored, they would run impossibly salick and silent in their huge cast-iron piston workings, one stroke/bang every four seconds. But ‘Steampunk’- like the american term for lorry ‘truck’ – was not a word in John’s vocabulary. I never once saw a flat-cap which was accompanied by a fancy moustache or skinny jeans at Casterton. It just didn’t happen. It wasn’t a secret society. Not at all. On the contrary, it was a free-for all for enthusiasts. Dogs were given water-bowls, we ate cakes and sausages, and there was no craft ale in sight. But it wasn’t digital. It was a yearly catch-up, and alongside the low-loaders and painted and polished ironwork, old farmers would lean on the idle ploughshares of their forefathers, kicking the mud off, putting the world to rights, and baring their souls quietly in the afternoon sun to eachother. John and Phil, Arthur Hinch, and the legendary Knight family, had put the event together lovingly for just this to happen, it seemed.

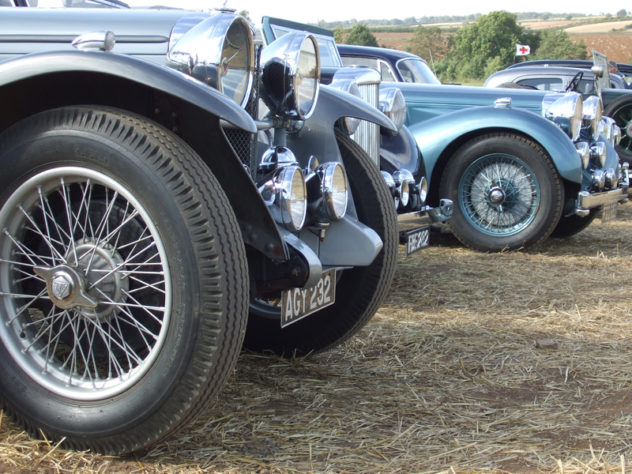

And I was always an honorary member. John taught me everything he knew, and as I started buying old cars of my own to restore, he would be just down the lane with tools and know-how, keeping a brotherly or paternal distance, and allowing me to make my own mistakes. Eventually, he had me panel-beat dents out of a fifties Fordson Dexter front-grill. ‘You’re the only one I would trust to do it right, Master Rupert’, was all I needed to realise that I was starting to be able to hold my own in a world of engineering experts. I had a long way to go, and looking back now, it seems I have come some of that way. ‘Things should be used’, was Uncle Phil’s motto which he passed down to first John, then me. ‘They shouldn’t be in museums, they should be getting dirty and dented in a field or on the road.’

The family continued to go on holiday in the long black 1924 Cottin Desgoutes Sedan they had. People would ask whether it was a Rolls Royce, whenever I had the privilege of being part of the passengers pulling-up at the roadside. It was the only one in the world, was what I knew. They had once found anothor, different model in Australia, and when they found a ‘Cottin’ entry in some old ‘Observer book of Motorcars’, it turned out to be their very car in the photo! An aluminium (unusual for 1922) body on an iron chassis.

Uncle Phil had rescued it from a scrapyard in the early 1950s, as I was inspired to do with my first three mini-vans (Austin and Morris mini, not BMW – perish the thought!) There was nothing wrong with it that a bit of ‘elbow grease’ couldn’t mend, according to him. Phil had replaced the engine with a WW2 ‘Lorry Engine’ in my early childhood, and the iconic vehicle had sat in their wooden garden shed-turned garage/workshop under covers until, finally, with high excitement, it was recommissioned. I was one of the first to ride in it. I was engaged in building a mechanno steam-car at the time, and Uncle Phil was helping me figure out the parrallel steering. I was eleven.

Somewhere around this time, I became ‘Master Rupert’, and John became ‘Mister John’. It was a transition between childhood and adulthood which we negotiated through comedy ranking. My sister Juliet became ‘Miss Juliet’, and ‘Master Bruce’ was my best friend and accomplice in all disaster-making, technical and otherwise. I think we had first decided that there was a military ranking, but this didn’t stick so well, although I still sometimes referred to him as ‘Field Marshall’. But John wasn’t any kind of class, rank, or superior person. There was no consciousness of this in him. Some of his best friends were old ladies who he diligently supported, gaining life wisdom, giving lifts, help, and entertainment to, and broadening, in lateral ways, his understanding of times gone-by, when his beloved machinery was in its heyday.

Stamford has a mid-lent fair. It is famous in its own right for being possibly the only town fair which has run continnuaously from the early middle ages until now without missing a year. As children, it was the highlight of our year. I went there as a kid, as a pubescent, and as an excruciated awkward teenager, looking for the girl of my dreams in the lights and whirling. But countless times – the most memorable ones – were spent walking down with John. We didn’t ever even see the stalls themselves, and what they were peddling, or the fun they were mechanising. John would make a beeline for the generators, power units, and lorrys which towed and powered the rigs. Atkinson, ERF, and Seddon, as well as Scammel and Ford populated his mind. But his one great love, apart fromn the buses and their history, of which he had a huge knowledge and massive collection, was the Foden lorry. Indeed ‘Foden’ was one of his last words, in the jumble of what must be the scariest hours in life.

We would pick our way through Gardner and Cummins power units – running sweetly and providing a livelihood for the showmen and their families year after year. Consumate professionals, clean engines, greased cogs, griease-smeared faces, tattered clothes. But when we would find a Foden, John’s eyes would light up and the stories and history would flow. He was a scholar on the subject, and the master of quite a few histories. But he never repeated himself. He knew what he had taught me, and I took pleasure in demonstrating that it had sunk in. He was an ambassador for technology, but he had a strong belief in people, and he knew, somehow, although he NEVER spoke about it, that we were all going to better place in the end.

And I used this knowledge too. I didn’t run away with the fair. It did occur to me, but instead, hitchiking around the UK and Europe in my teens and twenties, the lorry-drivers would be impressed that I knew their rigs, the challenges they were facing, the technical decisions they made to keep going. I would get dropped-off that extra mile down the road; they would get on their CB radios and organise another lift from the next truck-stop, ‘going my way’. I would even doss-down in the cargo once or twice, if I was in a pickle. The ‘journeyman’ life was something that stayed with me. Touring theatre shows, humanitarian relief-work, and international film work were all informed, for me, with the working best-practice which John instilled. Clean up after yourself. Leave things better-off than you found them…

John once joked to me: ‘the only bright lights in Stamford go like this: Red….Amber…Green…Amber…’ after I had returned from some foreign clime or big city. But John was one of my brightest lights in my life, and for others too. We are all continuously and forever indebted to him and his humble brilliance, approachability and wit, as well as his enthusiasm for life, improvisation, and people. He will be missed in many places, by people who he never heard of, but who have hopefully benefited through the work of people he inspired. I only hope that my work, which was so fundamentally inspired by him, has done him justice.

As well as me, his friends and his later-life love (after Foden lorries), his wife Leslie(!), John leaves behind him a 1948 Fordson Major, a 1924 Cottin Desgoutes Sedan, a 1972 Jaguar XJ6, my 1969 Morris Mini Van whose ownership we tag-teamed over two decades, and various other beautiful and unique objects, all of which he made sure went to good homes before he died.

For me, he leaves behind a lifetime legacy summed up by D.H. Lawrence in a poem I often quote:

“Things men have made with wakened hands,

and put soft life into

are awake through years with transferred touch,

and go on glowing

for long years.

And for this reason, some old things are lovely

warm still with the life of

forgotten men who made them.”

One of John’s favourite voices was that of Sandy Denny, who can be heard singing a favourite tune HERE: FAREWELL

John certainly left me better-off than he found me. God-speed, Mister John. Mind how you go.

(All Photos Courtesy of ‘Master Bruce’ Charlier)