This is the log of passages made by the 37ft Ketch Sandpiper, under the command of Rupert Allan, See also the ‘Voyages of the Ketch Sandpiper‘ community page on Facebook.

Chesapeake, Maryland, Virginia, The Great Dismal Swamp Canal and North Carolina.

The ‘Goose House’ on Bear Creek, from Matthew’s C&C 34 on the hard.

Sunday, 5th November 39.15.19. N 76.29.38W

‘Bear Creek Bridge, Bear Creek Bridge, Bear Creek Bridge, this is Yacht Sandpiper, requesting an opening.’

‘Sandpiper, Bear Creek Bridge, should be open for you in just a few minutes. What time can we expect you back, Captain?’

‘We won’t be coming back this time.’

‘Well, have a safe trip, Captain, Bear Creek Bridge-Sandpiper Out.’

We were finally leaving Bear Creek for the last time. As always with trips, the ‘final departure’ statement lacked conviction. I have always hated the accountability I feel when I describe the project before I initiate it. A statement of intention is always a weight tied on to the idea, an extra ten pound weight in an already up-to-the-limit rucksack, a cylinder suddenly misfiring in an already straining engine. People who ask about plans seem to have no idea how much energy life takes out of you to move it along. My heart sinks when I am asked to explain, and it feels as though I am inviting jeaopardy having to verballise rather than ‘get on’…

Sandpiper Itching to Leave

At two in the afternoon, after a tearful christening from Ted’s bottle of Corona beer over the fo’c’sle, we pulled of the dock at Sheltered Harbour Marina, the site of the old Owens Boatyard.

Textures of Sheltered Harbour

The boat had been there almost exactly a year. We had decided to leave, just to get ourselves off the dock, although there was no way we would now make Annapolis in daylight. Bodkin Creek seemed like a good option, though, and although we were still lacking some essential items from Baltimore, which I knew would cost us double to buy along the way, it was time to go.

39.15.12N 76.29.34W

39.15.12N 76.29.34W

I felt comfortable at the wheel of our 35ft Ketch, now. A confirmation that our speed log needed recalibrating, and that we did go at a speed which was at least vaguely comparable with the other boats, which had come with the sail of a few days before, was comforting. It was also comforting to know that when the sails were up, Sandpiper would do seven knots. We had nearly killed ourselves with the work on her over the last year and a half. We knew every inch of her. And now, as the creek opened out into the north western spur of Chesapeake Bay, our adventure was starting.

Chesapeake Bay, Famous Sailing, Fishing and Invasion Territory

Chesapeake Bay, Famous Sailing, Fishing and Invasion Territory

Chesapeake is not a bay, it is a two hundred by fifty mile inland sea, with a small opening at one end, which has the sea and naval port of Norfolk, VA, and Baltimore MD and Washington DC at the other. It is halfway down the east coast of the continental mass of North America. As I steered the boat, (with Dorry and Mik as crew in our floating house) into the shipping channel at the entrance to the harbour area of Baltimore, it felt very much like a first day at a big new job. Lots of things to get the measure of; application of hard-learned principles to brand-new situations, and a lot at stake – always the background possibility of life itself. The busy and massive commercial shipping which runs up the length of the Bay daily at four times the speed of the small craft passes strictly through dredged channels.

Chesapeake is one huge ex-oyster bed which has been destroyed by American commerce, and is now ‘protected’. It is a huge silted mudflat which is fed by Patapsco, Potomac, York and several other rivers. This mudflat is covered with an average of ten feet of water. The shipping channel is marked with huge iron and steel buoys.

Pay Attention to the Channel Markers; We later hit one like this at dawn in South Carolina

Although there is a huge risk of running aground, hitting another craft/buoy, or being sunk by ‘short’ waves brought about by wind on shallow water, very few people die on the Chesapeake. Indeed, any statistics not mentioning how many thousands of people are on the water per square mile are pointless. It is a very safe place. ( We have since met many a round-the-world sailor who came unstuck on the bay, and since that time of writing have myself narrowly dodged Hurricane Arthur on my return to the bay in 2014, 5000 miles later).

Close Enough! One of the many tall-ships plying this Atlantic corridor between Baltimore and Newport News/Hatteras

But you can still wreck somebody’s million dollar yacht, or have to pay to have your own sunken boat removed if you mess up, and that could ruin you. Luckily for me, Mik, who was able to join us for a couple of weeks has been on the water far more recently and regularly than I who have been slaving over the boat, and his presence was a godsend. It is easy to lose track of what is essential when there are different levels of essential-ness. By that I mean that your proximity to certain things in a certain place can blur your awareness of the golden rules and composition of a basic sailing boat. Mik was very good at gently reminding me in conference of many basics that I may have overlooked whilst wanting to make the most of availability of spares/items in Baltimore.

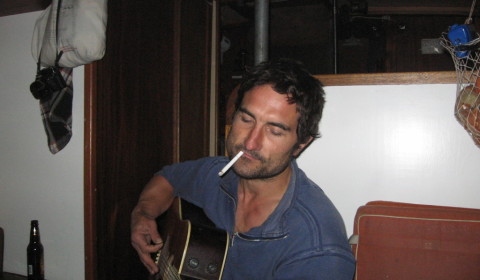

Mik

No Stopping!

The first leg of our voyage to Bodkin creek became pleasantly democratic. Focussing on the weak elements – the uncertainty of how the boat would perform, whether she would have the power and agility to get out of trouble – I spent a lot of time checking systems.

With Mik at the helm, and Dorry with the chart and the new GPS, we made fairly good time in the uninspiring reaches of Baltimore roadway.

Bodkin Creek seemed sheltered and convenient, and the anchor was never a risk with the weather we were promised. We made it into the creek with the first of the several confusions I was to have with chart scale and, more importantly, ‘compass swinging’. I had installed a stereo in the boat, and positioned the magnetic speakers so as not to affect the compass reading. But that was only when we were pointing a particular way. The compass on a boat is positioned amongst a delicate network of ‘laylines’ of force created by different ferrous manifestations, ranging from steel bars to electric clocks. To keep it steady, it is possible to ‘balance’ the effects of these forces with small magnets in the compass. But one solution does not work for all directions. You correct it by moving the boat through the points (North, East, South, West), adjusting magnets at each point, then noting and putting-up with the minimised inaccuracies.

Helm position and speakers, taken from near the compass. Matthew on Sandpiper in Bear Creek.

Helm position and speakers, taken from near the compass. Matthew on Sandpiper in Bear Creek.

We managed to get around and into the creek, and decided to drop the hook right in the middle of the creek. It was getting dark, and I had decided to use the Danforth Anchor. Anchoring is a greatly debated subject. I had read many books and taken much advice on the subject of which anchor was best for which type of ‘holding ground’ and how big that anchor should be per ton or sometimes per foot of boat, per knot of wind expected, and or how many feet of chain I should use. The general rule seems to be Danforth for really soft silt, with always as much chain as can be used safely without making it impossible to haul up. The CQR anchor which we also have is said to be best for sand, grass bottoms and hard mud. We also bought a ‘Maxx’ anchor cheap, which I am researching, and a lovely plain, strong bronze windlass, which we fitted.

Our ‘ground tackle’. Anchors: CQR shipped to port, Danforth to starboard, and our lovely Plath Windlass from Bacon Sails secondhand bargain shelf…

I controlled the boat from the helm and sent Mik up to drop the hook and 35ft of chain and rode (length of chain is joined to rope, with anchor at the other end. The weight of the chain makes the anchor dig in or ‘set’).

Dorry cooked us some food, and we turned in about an hour after sunset. We were on our way!

Monday, 6th November

Sunrise the next day was cold, stressful (what if we’d run the battery down and couldn’t start the engine? What if the anchor was snagged?). Even though there was not a spot of wind, I had been on deck three or four times in the night to check that we weren’t ‘dragging’. Dawn, however, was magical:

Bodkin Creek, 39.07.03N 76.26.32W

Bodkin Creek, 39.07.03N 76.26.32W

Idyllic!

We had spent the night in a beautiful place, and although we were thinking about getting into Annapolis, how much further we could get that day was in the balance. There was a lot of shopping to do in busy Annapolis, and the port to get into. The engine started up without a hitch, we pulled forward, up with the anchor, and out of the creek we went.

Dorry soon had the coffee steaming away in the mugs, and getting out, as we are discovering, is always easier than getting in.

We tracked around some shoals in the mouth of the creek and motored out into the shipping channel. Very soon the Bay Bridge was in sight, and just as we went under it the phone rang and it was Hans, of Whisper who, the previous week had made it as far as Norfolk before stopping for repairs.

Annapolis Bay Bridge

An uneventful run into Annapolis, but with some shoal scraping brought us into the City Dock, and we pulled up outside Fawcetts Chandlery. New halyards and $400 later, we pulled out and set off for what we had decided would probably be an overnighter as far south as possible.

Herring Bay was a stop off possibility, but it was 3.45pm and we would probably not make it in daylight. We thought that it would be best to expect an overnighter, and so we set about preparing for the watches. The thermos was dusted down, waypoints were found on the chart, and the foul weather gear and lifelines prepared.

We had been told that the reach between Point Lookout and Point No Point was riddled with uncharted obstacles, so we were scheduling the night around our arrival there.

Mik had spent some time getting the GPS up and running, and it was good to have his well-oiled navigation head, as it had been a while since I had navigated by longitude and latitude. The night passed, and once the old watch habit had been remembered, the sense of a real voyage started to infect the boat. I did the first watch, sending Mick down below for what turned out to be little more than an hour and a half. During this time – we caught the tide down the bay, and were making better time – we passed the Naval target area (38.37.02N 76.27.40W), which I was trying to use as a waypoint, and as we went past, try to keep the right side of the buoys, several huge black shapes could be made out, not marked on the chart, which was creepy.

Chesapeake Bay at Night

The night was spent motoring only, and Dorry took the ‘sleep watch’, so she could be compos-mentis for the next day when we might not be. This was the first real test of our new handheld GPS/VHF Radio, and it performed very well. We had gone off the page of our Garmin Plotter, so it was redundant, as it only had the memory cards for North and Mid Chesapeake, and we were starting to get well down the Bay.

Tuesday 7th November

As the first light started to glow in the east, it became clear that we could easily make it beyond where we had hoped. The engine was purring away (in a loud Italian way), and we had a whole day of daylight before us. Rain was forecast for the late afternoon, so we thought we would try and make it into Deltaville. The main event of the day was the fixing of the propane swap-over valve, which had always been overcomplicated, supposedly in the interests of safety. One of its delicate plastic mechanisms had broken, producing a gas leak, so I dismantled it, cleaned it, and modified it to be simpler and better. It was important to head south around shoals before taking a westerly course, and we put Mick to sleep for the afternoon, and watched the Bay pass us by.

Dorry on the Helm

Dorry on the Helm

The channel into Deltaville was narrow but well-marked, and we rounded the inner end of the breakwater looking for Waldens Marina, which Dorry had found to be the cheapest. We were pointed to a pier head by a liveaboard woman, and when we went to explore, met a very friendly and helpful worker who was just finishing epoxying a wooden spar. Clifton. He told us the shape of the place, hints and tips, and leant us his key to the showers. We seemed to have found ourselves a much-needed stop-off, with a chandlery (which I was not allowed to spend too much time in!), and decided to stay two nights. Our head (marine toilet – flushing by hand on a pump system into either holding tank or through-hull as lobster food) had been causing problems, and was siphoning back into the washroom (lovely), so I needed to spend some time reassessing that situation, and preparing for the holding tank to be pumped out. Waldens had pumpout.

Wednesday, 8th November 37.57.14.N 76.23.09W

The next day, Mick started replacing our halyards with the new ones, but lost a bitter end and called me from work in the head to haul up the mainmast in the Bosun’s Seat. It was a good chance for checks on rigging and running lights, and it gave me a great view over the breakwater, where I saw fog rolling in from the Bay over the marker buoys, to engulf us all a few seconds later.

Rigging Checks, while I was at it, harness courtesy of Fallen Angel Theatre Company

Dorry had walked all the way to Deltaville for groceries – which turned out to be four miles away – and came back glowing, but nobody was in great spirits. I had spent a lot of the day amongst slurry, and Dorry had only got a lift for two of her eight miles, Deltaville population amounted to about ten people, and fourteen marinas. But she did buy what became known as her ‘Deltaville Boots’. We were soon to be nearing the Great Dismal Swamp, where there were options to be discussed, and decisions to be made as to where we would aim for as a departure point for Mik. We spent a couple of hours in the bar over a beer or two, pawing over the charts.

After a lazy morning we picked our way out of Deltaville, and ‘bent’ the fore and mizzen sails as immediately as possible to the north easterly which died out in mid afternoon. We decided to leave a clear day for the ICW entrance, wanting to get to the first rising lock – Deep Creek at the end of the next day. So at the end of our best sailing day yet we carefully negotiated the buoys of the entrance to Broad Creek on the York River. Once again, the compass proved capricious on south westerly bearings, and we ran soft aground twice before finally dropping the Danforth in about five feet of water – six inches below the keel. It was a peaceful night, but I was slightly disturbed by tidal possibilities in such shallow waters.

Thursday 9th November

The next morning was not stressful, though, and dawn brought another beautiful panorama:

Broad Creek at Dawn 37.10.29N 76.24.46W

Broad Creek at Dawn 37.10.29N 76.24.46W

We weighed anchor and carefully made our way back out of the creek. A pleasant reach on a north westerly wind took us towards Norfolk, and we were soon approaching Hampton Roads shipping lanes. Mik was at the wheel, enjoying seeing the shores of Norfolk naval base, where he spent some of his childhood, and regaling us with tales of fishing and crabbing as a boy.

Soon we started to see evidence of the ocean port, and it was quite nerve wracking to jostle through the busy channel. We decided to call in at the marina near Hospital Point – the official start of the Dismal Swamp ICW – where Hans and Kristen, on Whisper, were awaiting parts on the hard. Again the bearing was a south-westerly orientation, so the compass was not as useful as it could have been. Dorry was desperate to get off the boat, and as we encountered our first serious current, shoals and large docks, I felt a lot of pressure in the following wind as we came in to dock.

We made it, with a modicum of indignity, and a few hours were spent onshore, dispelling cabin fever, and catching up with the crew of Whisper. Darkness was not far off, and so we decided to pull off, and try to get to the first stop on the Great Dismal Swamp, Deep Creek Lock, ready for an 8.30am opening the next day.

As we navigated around the port of Norfolk what I had studied so avidly on the chart shaped itself into reality. We passed several Navy ships, one of which Mik was very familiar with…

As we navigated around the port of Norfolk what I had studied so avidly on the chart shaped itself into reality. We passed several Navy ships, one of which Mik was very familiar with…

The route of the ICW was not completely clear, as one might expect, because of the several rivers and creeks in Norfolk, and because of its busy-ness. There was a regenerated waterfront which we passed along, reminding me of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, and then, as the lifting bridges appeared ahead, the river current started to feel on the helm, and the shore passed slower and slower. The two lifting bridges were of an unusual design; the whole middle section was lifted upwards laterally by huge pulleys at the top of a tower on each side of the river. As the darkness fell, and after making it through the final bridge which was a bascule (swing) bridge, the sudden turn to the right was upon us sooner than expected. This was the first experience of the sometimes unclear ICW channel and route markers, and it marked the start of a stressful few miles in the dark.

The route of the ICW was not completely clear, as one might expect, because of the several rivers and creeks in Norfolk, and because of its busy-ness. There was a regenerated waterfront which we passed along, reminding me of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, and then, as the lifting bridges appeared ahead, the river current started to feel on the helm, and the shore passed slower and slower. The two lifting bridges were of an unusual design; the whole middle section was lifted upwards laterally by huge pulleys at the top of a tower on each side of the river. As the darkness fell, and after making it through the final bridge which was a bascule (swing) bridge, the sudden turn to the right was upon us sooner than expected. This was the first experience of the sometimes unclear ICW channel and route markers, and it marked the start of a stressful few miles in the dark.

It is not permitted, as I later found out, to travel on the Great Dismal Swamp route at night. I can now understand why. It had been shoaled and twisting on the river before we turned into the Dismal Swamp, but now it was even narrower. With the help of the searchlight we picked our way slowly along, using our searchlight, and eventually the lock gate loomed above us as we tried to find a place to tie up. There was nothing by the lock, so we went back to a piling we had seen, as the only anchorage was occupied by a ketch which had passed us in Norfolk. As I fetched the piling, it was sheer luck which made me notice a black shape looming out of the water. I slammed the helm down and we cleared a very sturdy piling set, which we were able to stern-line onto. I was learning how slowly to take things when in doubt!

It is not permitted, as I later found out, to travel on the Great Dismal Swamp route at night. I can now understand why. It had been shoaled and twisting on the river before we turned into the Dismal Swamp, but now it was even narrower. With the help of the searchlight we picked our way slowly along, using our searchlight, and eventually the lock gate loomed above us as we tried to find a place to tie up. There was nothing by the lock, so we went back to a piling we had seen, as the only anchorage was occupied by a ketch which had passed us in Norfolk. As I fetched the piling, it was sheer luck which made me notice a black shape looming out of the water. I slammed the helm down and we cleared a very sturdy piling set, which we were able to stern-line onto. I was learning how slowly to take things when in doubt!

We tied up, and I broke out the Zodiac, ready for a trip ashore to the Mexican restaurant recommended by Skipper Bob, which I had promised Dorry earlier on that afternoon.

Deep Creek Lock

Deep Creek Lock

It was great fun, and a proper family restaurant, and we ate well, drank San Miguel and Dos Equiis, and enjoyed the change of scene.

Mik stayed on the boat, and was fast asleep after a bit of stargazing, when we got back.

Friday, 10th November

The next morning we were up at dawn for the lock, which I wanted to be ready for.

The gates opened, and we waited with lines for other boats to go on ahead and into the basin. I was sizing up the manoeuvering. The boat before – the ketch – went up to the far end of the lock to allow for us and others behind.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

As the water started to flow in – the gates had shut behind us – he started to struggle from the wash created by the gates at that end. The lock keeper came past and shouted to me to straighten and lock off the helm. I watched what this did to our boat to keep it straight, rather than bucking against the wall of the lock. As we neared the top level, and I had a chance to look around me at the six boats in the lock with us, the lock keeper invited us all go onshore whilst pressures equalised.

He was a great character, obviously loved his job, and was dressed in a proper outfit like a Canadian Mountee, complete with aviator shades. He had prepared coffee and Danish pastries – obviously a standard procedure with him, and it was a rare treat after such a stressful morning! It was good to meet people with the same ideas as us, and an excellent welcome to the Great Dismal Swamp. As we pulled out of the lock, I asked the lock keeper why it was called the ‘Great Dismal’ swamp. It was an advantage to be pulling off slowly, as we got pretty much the full story about how it came to be, with the lock keeper strolling along the quay to the end fence, quoting archaic ‘founding fathers’. Obviously a personal set-piece, and highly enlightening and amusing it was, too. The experience was only marred by me then not realising that we had to wait for him to drive round and open the bridge as well, and I got shouted at by the skipper of a very beautiful Down-Easter 32, (who we were to come across again, and who proved to be the source of many a wry comment, in a few difficult situations) as we inadvertently ‘jumped the queue’.

It was demoralizing, but had been expected that, as all the boats pulled away from the lock, we were left behind. I reckoned we could do five knots max, and some of these overpowered American boats were really fast and well-suited to all-day motoring. I knew we were faster sailing than motoring, and that there would be more progress made by forking left, (east) to seaward, down the ‘Virginia Cut’ route via Kittihawk and the Currituck Sound. But we were all taken with the idea of the Great Dismal Swamp Route, and Elizabeth City, as well as sounding welcoming and charming, had become the planned drop-off point for Mik. We got used to the wakes of passing boats but not without the inevitable crashing of falling objects below decks as we gyrated from side to side.

It was demoralizing, but had been expected that, as all the boats pulled away from the lock, we were left behind. I reckoned we could do five knots max, and some of these overpowered American boats were really fast and well-suited to all-day motoring. I knew we were faster sailing than motoring, and that there would be more progress made by forking left, (east) to seaward, down the ‘Virginia Cut’ route via Kittihawk and the Currituck Sound. But we were all taken with the idea of the Great Dismal Swamp Route, and Elizabeth City, as well as sounding welcoming and charming, had become the planned drop-off point for Mik. We got used to the wakes of passing boats but not without the inevitable crashing of falling objects below decks as we gyrated from side to side.

The Superintendent’s House

The Superintendent’s House

We knew it was not far to the ‘North Carolina Welcome Station’ and had read that it was well-organised and worth a visit. The passing of the State line encouraged me to break out the old Jamaican standard ‘Oh Carolina’ on the stereo, and with Rudi Rodriguez’s trombone as soundtrack, it was fun to feel like we were finally approaching Confederate country. Our mood was broken a little by finding the welcome station dock full with other boats, but our forced move-on at least put us ‘ahead’ of them. We decided to push on for South Mills lock – which would drop us back down a level on the other side of the Great Dismal ‘cut’, and we got there in good tine for the opening. We had waited a bridge opening earlier in the afternoon, and taken the chance to look around a charity shop whilst waiting, and this had given us a feel of how the ICW ‘surfaces’ at random and often unlikely points in the American ‘interior’. A lot of people wave and several stare – either resentfully or wistfully.

South Mills Lock had its fair share of onlookers, and the experience here was very different from the start of the day at Deep Creek. The lock keeper was a lot more patronising and less clear about where he wanted the boats. We talked to people at the lock and reached a consensus that there was no chance of reaching an anchorage significantly further on with what we had left of the daylight, and that there was a mooring and/or anchorage just the other side of the lock in an old loading canal.

South Mills Lock had its fair share of onlookers, and the experience here was very different from the start of the day at Deep Creek. The lock keeper was a lot more patronising and less clear about where he wanted the boats. We talked to people at the lock and reached a consensus that there was no chance of reaching an anchorage significantly further on with what we had left of the daylight, and that there was a mooring and/or anchorage just the other side of the lock in an old loading canal.

After letting all the other boats pass us and bustle onwards down the canal, we took a starboard turn into the basin, which was clear, moored up, and I set about servicing the head yet again.

We had a comfortable night there, nevertheless, and once we had finished cleaning in the morning, we set off into the real ‘swamp’ of this route. Twisting and winding, with islands mid-chanel, and no feasible ‘ground’ to tread on but the everlasting mess of tree-roots, we began to see how the pioneers had died in their droves, and how dangerous it must have been for deserters fleeing north from the civil war. We were entering alligator country for the first time.

After half a day, the river twisted out into a wide sound, which turned into a large lake, the other end of which was Elizabeth City – our final destination with Mik. We pulled into a very pleasant but basic marina to get fuel. It was a difficult manoeuvre, with the wind behind us in a narrow chanel, but testimony to the skills we were acquiring that we got in – and out again – without a hitch. The wind was getting up – there was a storm predicted, and we were trying to get to Elizabeth City, where the famous welcome committee would give us cheese and wine, and we would meet other mariners. It started raining, and didn’t stop…

It felt like hours…

We were the last boat to come through the Elizabeth River swing bridge before the storm proper started, and, with all the easy berths taken by other boats (free mooring at Elizabeth City!), we had to round up on Mariners Wharf three times against the increasing gusts before getting a rope secured fore and aft.

We were the last boat to come through the Elizabeth River swing bridge before the storm proper started, and, with all the easy berths taken by other boats (free mooring at Elizabeth City!), we had to round up on Mariners Wharf three times against the increasing gusts before getting a rope secured fore and aft.

Elizabeth City Swing Bridge

Tired, wet, and grumpy at the shouting of stressful mooring processes, we shut the hatches, fetched out the rum flagon donated by Ted in Dundalk, and settled in to contented oblivion while the storm raged…

And Raged…

And Raged…

So far, So good.

APPENDIX:

Mik’s account.

Okay, the first half of November I helped my friends Rupert and Dorrie get started on their way south on their 35 foot ketch, and I stayed with them until Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

We started in Baltimore, or rather, Dundalk, a semi-industrial suburb of Baltimore. There were, of course, delays before we could untie the dock lines and push off. The biggest of these was the discovery of a slow leak in the housing for the boat’s centerboard (a moveable keel extension that swings up into a watertight box in the bilge but still under the waterline.) The leak itself wasn’t bad, but it would only get worse, so the thing to do was to fix it “at home”, where we knew where to get stainless steel bolts, caulking, and most importantly, a cheap boat lift.

The complication was that the marina’s only Travel-lift operator was going to Canada for a few days on business, so there we were, hanging high and dry for 3 days, 12 tons of boat swinging clear on two industrial nylon straps 5 feet above the concrete. The first night the wind picked up quite a bit, and the boat did sway and the cables did creak. I lied in my sleeping bag imagining the boat dropping, estimating where the masts would punch through and which part of the deck would be torn open, and, over tea in the morning, it turned out that each of us had been silently making the same calculations. It wouldn’t have been any fun to wake up crushed, not even a little bit.

The next night, with the boat’s decks still high in the air, way up just under the crossbeams of the Travel-lift, I was awakened by footsteps overhead. At first I thought it had to be Rupert, but then he appeared out of the forward cabin, looking rather groggy by the dim lamplight. I rolled out of my bag and opened the companionway hatch to see who was on deck before Rupert told me that Dorrie had gone up the forward hatch (and down the ladder and across the boatyard to the head). “Oh,” I said, and then, looking for the word “intruders,” I added, “I thought we were being boarded by . . . uh, pirates.” Rupert replied that at the height we were at on the Travel-lift, it would have to have been pilots. Pretty clever pun for the middle of the night, don’t you think?

The night we put the boat back into the water we had a little hobo party. Bo, who lives in a sweet little trailer with his dog near the boatyard and does diesel work and other boat jobs, found a bunch of scrap wood to burn in a barrel in his “front yard.” We had a big pot of stew, a variety of beers, and 8 or 9 of our marina friends standing around the burning barrel, our front sides roasting and our back sides chilling. It was a much more fitting going-away party than a yuppie restaurant dinner ever could have been.

Sunday afternoon, we finally pushed off. We didn’t go very far; before sundown we made it only a few miles to an anchorage in lovely Bodkin Creek, but we had started, and that was the important thing. We could have easily spent the next month in Dundalk preparing and improving the boat, but with the advancing season and the knowledge that a boat is never, ever completely as ready as you’d like it to be, we started. Rupert and Dorrie had been restoring the boat for almost two years, coming back and forth from their home in Wales and illustration and movie-industry jobs in London, Africa, and India, so, except for a recent test sail and the initial moving of the boat after purchase, this was their first pleasure sail. After almost two years of preparation, sometimes, ready or not, you just have to start your adventure.

In the morning we motored down to Annapolis to pick up some boat gear (new line for the halyards, a radar reflector, etc.), and then in the afternoon we were off again, headed for the bottom of bay (geographically speaking, of course).

There was no wind to speak of, so we motored – for 24 hours straight, all the way to Deltaville, Virginia. It wasn’t nearly as fun as sailing would have been, but I enjoyed it thoroughly. A couple of hours into the night the moon broke through the clouds, so the water was silver and black, and there were a fair number of stars overhead. It was cold – a T shirt, thick cotton henley, wool sweater, fleece vest, fleece-lined foul weather coat, and I still had the sniffles – but it was good to be out on the water at night, all night: it brought me back to my Navy days, nearly 30 years ago, and I felt more like me. When I went below to rest, I lay on the settee still wearing my jacket, my shoes, and eyeglasses, and I drifted off to sleep by the sound of the old long-stroke diesel loudly thump-thumping away, pushing 12 tons of boat through the night. Again, it brought back memories of my Navy days, youthful days, days of discovery and, if not adventure, awareness that you are indeed alive.

The boat has wheel steering, aft in the cockpit, tilted back about 10 degrees. You can sit on the coaming behind it and steer, or you can stand in front of the wheel, reaching behind you with both hands. For slight adjustments, though, or to hold the course, you can lean back against the wheel and steer with a little twist of your hips. So, although we used the charted buoys and GPS to find our way through the night, we truly could say we steered “by the seat of our pants.”

The next night, just before both darkness and the rain fell, we tied up to the T-head of marina near Deltaville. The rest of that big dock (and the boatslips on both sides) were covered with a tall tin roof over a sturdy frame of 4×4’s, lit just sufficiently by electric lamps in the rafters. We were tired, but we had a beer, and under the rain tapping on the roof in that shadowy boathouse, it was good. We stayed there the whole next day, fixing a propane leak and the overflowing (sewage) holding tank. That night, after listening to the latest weather report, we walked to a nearby restaurant/bar and had a beer while we spread out various charts and cruising guidebooks and came up with a plan for the next few days.

In the morning, without rushing, we motored out of the marina and then hoisted sail. It was just a little bumpy until we got out into deeper water, and then, in the afternoon, the wind eased more and more until they disappeared near sunset. That was okay, though, because we were going to navigate a narrow, twisting channel into an anchorage for the night.

We were able to make out the lighted buoys and match them up with the charts, but it was a little bit harder to locate the daymarkers on the edges of the channel. We’d scan the blackness with a strong flashlight, and when the daymarkers’ reflective green or red paint would catch our eyes, we’d have an idea of where they were until we could lock the flashlight on them. It’s kind of fun, like putting together a jigsaw puzzle with a time limit. We crawled past the markers into the creek, and then pointed into a shallow side creek for a recommended anchorage. Even with the strong flashlight (no kidding, it’s 1,000,000 candlepower) we couldn’t quite make out the borders of the creek, and there was no way we could visually make out the channel. So, we did what any other sailor would do: we ran aground. Twice. It was no big deal; we were feeling our way in with the depthsounder, the bottom was mud, the water was pond-calm, and both times we got ourselves off by standing on the toerails outside of the shrouds and rocking the boat from side to side. Running aground is not something you’d want to do intentionally, but under these circumstances it just added to the satisfaction of finally finding a protected anchorage.

We made our way to Norfolk, where we had a brief rendezvous with our friends Hans and Kristen. They had started south a week before us but had planned to haul out in Norfolk to replace a bent prop shaft. While the work was being done they were staying at their friends’ home, with central heat, hot showers, cable TV, and internet access, all of which they reminded us as often as they could.

We continued on, past the ships in the Navy yards and into the Intra Coastal Waterway. We opted for the Dismal Swamp Canal route, which Rupert enjoyed more than he thought he would. Much of it is a couple of miles of straight line, a slight turn, and another couple of straight miles, but it’s mostly tree-lined and quiet, like a water-road through the country. There is absolutely nothing on it terribly exciting, but putt-putting along on a mild autumn day, the sun shining and the foliage in full color, it makes for a pleasant day. And there are things to look at and catch your interest, like the grandfather and maybe 3-year-old grandson on the banks, fishing – the little boy saw us coming, began waving and say, “Hi!,” “Hi!,” “Hi!,” about 47 times, and then, the moment we came abeam and started to pass, switched to “Bye!, “Bye!” another 47 times. And there was the .22 rifle target, human-shaped and riddled with holes, set up on one side of the canal across from the well-used back porch of a small house. Among the trees there were some small houses, and some bigger ones, most with a small dock on the canal, maybe a canoe or a small skiff pulled up on the lawn, a picnic table under the trees, and you couldn’t help but wonder about the stories behind them all. For how long had these fun-looking little properties been in the family, and were they full of happy memories or family feuds? Those kind of lazy thoughts rolled through our heads, and the day passed pleasantly.

The next day, however, the warm, T-shirt in the November sun weather disappeared, shoved away by cold, and wind, and patches of heavy rain. Out of the canal, we motored on through the twists and turns of the ever-widening river. Even though the weather was hardly enjoyable, and our foul-weather gear kept us only marginally comfortable, the day was kind of fun. At one point, Dorrie came up from below and surprised Rupert and me with hot mugs of stewed tomatoes and rice, and life was real good.

We made Elizabeth City, North Carolina just before nightfall. The cold wind was gusting, the colder rain was pelting, and it took us three approaches to the town dock before we got a line made. We tied up, set the fenders, and clambered below, slamming the companionway hatch shut behind us. The skipper deemed it necessary to distribute rations of rum for medical and morale purposes, and after quick deliberation the crew reluctantly concurred. Then, as a preemptive measure against the night’s chill sure to come, we considered it only prudent to force down a beer or two. Down from the hook on the bulkhead came the guitar, out from the case in the gear hammock overhead came the flute, and out from the “ship’s stores” came more, and more, beer. So, while the wind jostled the boat against the dock lines and the rain pattered on the cabin roof, we sang songs like Me and Bobby McGee, Twist and Shout, and Should I Stay or Should I Go. Yes, we did get progressively louder and the choruses morphed from singing into screaming, but, oh well. Since Hans and Kristen had donated the beer on board (the overflow from their going-away party), we called them on the cell phone and told them to hurry up and catch up, ‘cause, dammit, we were running out of beer!

That night was great fun, though it wasn’t Rupert and Dorrie’s music per se that made it so. The relaxed feeling among friends, the intimacy of people revealing themselves through music played and songs sung, the snug boat cabin dimly lit by a kerosene lamp and one small, battery-draining light, and the alcohol warming us maybe more effectively than the propane heater on the floor; all of that helped, but that still wasn’t what made it so fun. The best part of it all was watching Rupert and Dorrie.

They make quite a pair. He’s thick-chested and well-muscled, almost swarthy, and although he’s soft-spoken and more gentle than many men, there’s no missing the fact that there’s plenty of testosterone working in him. She’s long-legged and clearly a woman, and it shows even more when she gets girlishly excited over little things. With his deep voice, strongly strumming his guitar, and with her womanly voice and enthusiastic flute, they balanced each other, like yin and yang. (But then again, maybe I was just drunk.)

Dorrie likes boats and the sea, but this boat, this trip along the coast and into the Caribbean, is Rupert’s dream. She’s there because of her man. She’s almost always bright-eyed and smiling, and she handles lines and takes the helm, and if you turn around and blink your eyes and she’s offering you “a spot of tea” or a plate of porridge with raisins and banana and honey, or bagels with slices of avocado or tomah-toes, or a fish curry, or something else good. One morning, I heard someone moving about in the galley, so I rolled over in my sleeping bag to find Dorrie there in front of me, handing me my morning tea – my first thought (and it came right out of my mouth) was, “I’m going to tell my dad about this!”

Elizabeth City is a nice little town with a free city dock along a park and a group of volunteer senior citizens who not only direct boaters to the cities amenities but also throw casual wine and cheese parties whenever at least four boats show up. They’ve been doing it for the past 23 years – that’s a lot of boats! One guy, Fred Fearling, who seemed to be the oldest, has the same last name of one of the downtown streets. I asked him if he’s lived his whole life there, and he told me, deadpan and looking straight into my eyes, “I don’t know . . . I haven’t died yet.” I laughed and told him that was a good answer. Again, deadpan, “That was a stupid question.”

Rupert and Dorrie continued south, and Hans and Kristen caught up with them soon, but my little vacation was over. They’d invited me to go all the way, but I just can’t, not this year. For one thing, I want to work on my boat to get it ready for my trip south.

People say sailboat cruising is a great way to visit other places, other cultures, other realities, but on this little trip I inadvertently discovered that the expense of a cruising boat and the effort of developing boating skills are unnecessary. If you want to see other cultures and be immersed in other realities, all you have to do is ride an interstate bus through the night. Sheesh!

In the Norfolk terminal, waiting for a transfer, was a young woman standing just a few feet away from me. A young man approached her, bummed a cigarette, and began a conversation that I couldn’t help but overhear. They quickly discovered they had a lot in common, though it wasn’t their hometowns or taste in music or anything like that. No, it turns out that they had been in a lot of the same jails. Yep, they were chatting away about which jails had the best food, the worst beds, and so on. We all got on the bus, and I could hear them quietly continuing their conversation. We got off the bus in Richmond for another transfer, and they were still talking about jails! They looked to be in their early twenties – how many jails could they have been in?! Yep, a match made in heaven. And there were two women, traveling separately, one in her twenties and one in her thirties, wearing not comfortable sweatpants but pajamas and big fuzzy slippers; the obviously slow-witted adult woman who should not have been traveling alone (she was going up and down the aisle giggling, making noises like a 5-year-old entertaining herself, talking with herself by pretending to be two people, and so on); and half a bus-load of people having casual conversations on their cell phone all through the night – who in the world are they talking to at 4 in the morning? Yes, there were a number of “regular” people, even a few Grandma types, but there were also a handful of slack-jawed young men who looked like they haven’t had a haircut, laundry service, or a job in months, carrying their possessions in torn plastic garbage bags. Policy-making government officials should be required to ride an interstate bus on a regular basis. Maybe I’ll sell my boat, buy a bunch of bus tickets, and write a book about it . . .