Tents as far as the eye can see…

Introduction

As Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Uganda, our presence in the country involves two arms of activity which are the benchmark of the OpenStreetMap democratic ethos. These are Capacity-Building (Training) and Data Collection (Mapping). The partnership with USSD allows us to strongly pursue these aims in with significant impact, amongst refugee and host communities in Northern Uganda.

We train partners and community members in the tools of OpenStreetMap (OSM), a global online ‘wiki’ map empowering under-served communities in technological skills, and increasingly used for humanitarian relief. These participants have local knowledge and techniques which they can bring to the mapping process, giving ground-level information about how their communities are served for amenities.

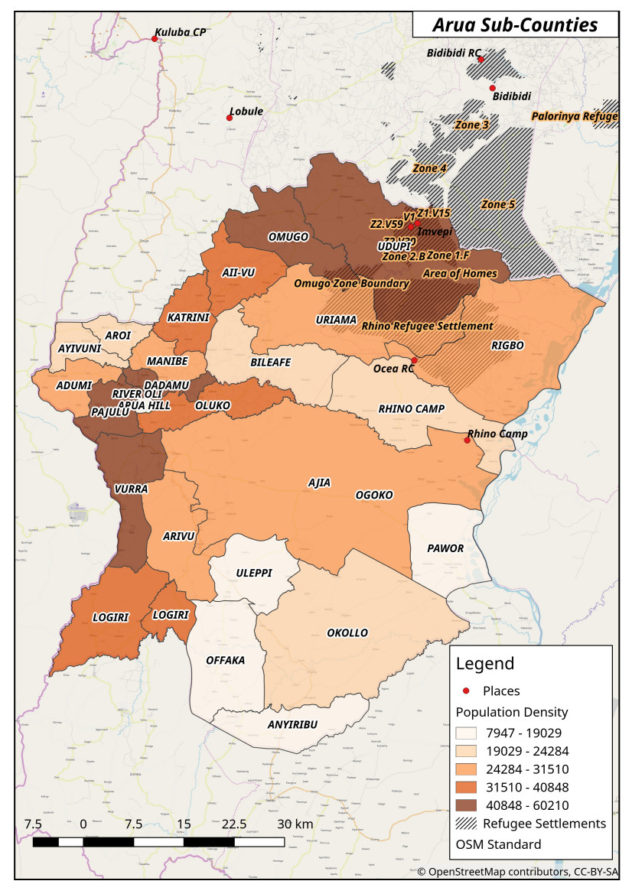

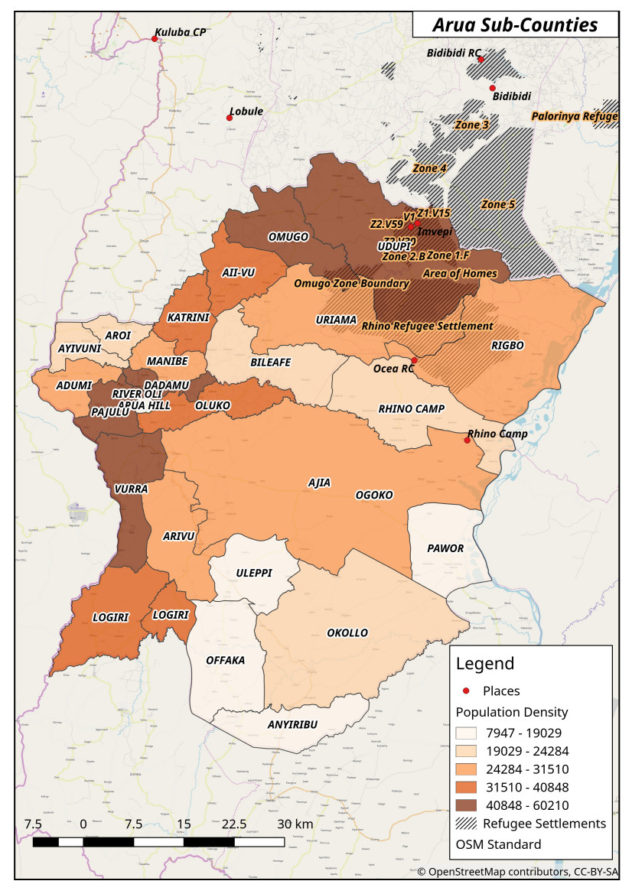

During the month of November and early December, HOT conducted field training, classroom training, and field-mapping amongst communities in the Refugee-Hosting communities of the Arua District. This is part of an ongoing HOT project, funded by the US State Department, called ‘Crowd-Sourcing Non-Settlement Refugee Data’, and locally referred-to as ‘HOT Uganda Community Mapping’. The project aims to identify Key Geo-Spatial Indicators of need and resilience amongst and between Refugee Settlements and Hosting Communities. Click HERE for some interactive OSM maps of our work in Arua District.

Background

This is a report on the first three weeks of field mapping operations in Arua, the first of the northern districts of Uganda which HOT intends to map. Arua has a complex refugee community where refugees live in settlements as well as amongst the community.

The management of this project, to which partners and even community members are encouraged to contribute, focuses on the collaborative integration of different datasets. These are across sectors and agencies, and are all brought into an openly-shared resource: OpenStreetMap. Data is mainly collected through lightweight Open Source Smartphone apps. We teach users to install the apps, design surveys, and use them in the field. The outcomes are both data-collection and ongoing support in the use, sharing, and manipulation of that data.

Project Objectives

1) Data collection: To ensure transparent and coordinated service provision through authenticity and collaboration with local communities.

2) Capacity-Building: To initiate a two-fold approach of enabling partners across sectors to adopt OpenStreetMap conventions, methods and tools into their own workflows (by training and ongoing support) and by initiating field-mapping data collection at community level, engaging members of both Refugee and Hosting communities on the ground.

3) Sustainability: to Create a Pilot Model for Ongoing Work. Because of the way community mapping can give a field intimacy missed by ‘top-down’ NGO ‘partner’ surveys, we can show a very granular technique for accountability and gaps in critical service. There are many agencies in Uganda who recognise the need for this. This project aims to showcase this technique.

Mapping Objectives

Goal: Field Mapping of Camp and Non-Camp Refugees in all hosting sub-counties, to record Geo-Spatial Indicators of gaps in service-provision to precarious communities.

How:

Universally Conventional Map resource creation

Data collected: Community Characteristics (Population, Movement, WASH, Health, Education, CBI, SGBV Risk Indicators, Refugee Livelihood and Movement.

Training in the Community:

The first training day, held in the field at Omugo Subcounty Offices, was used as a training in data collection and as a Surveyor selection process. All the usual challenges of Field Mapathons were expected and encountered, including generator and ‘MS Windows’ issues, water and rural access to WiFi (mass Smartphone tethering used, as the most secure, contingent and accessible method).

HOT Uganda team manager Deogratias Teaching Tasking Manager to Refugees and Locals

Viola (Refugee Community) and Jabo (Hosting Community) editing their own home data in OpenStreetMap iD editor

Participants were introduced to OSM data collection in the context of their own community needs, with the intention that this would build an accurate map which addresses presence of WASH, Education, Healthcare, and Cash-Based Intervention amenities in relation to both host and refugee communities in the district. 55 people participated.

Surveyors Learning OSMAND: how to identify ‘Blue-Dot’ offline Satellite Position on their Smartphones using OSM for Android

25th November 2017, Field Mapping Inception Starts

Data collection was implemented the next day with the selected candidates. This continues to date. Complementing this exercise is the continuation of OSM Open Workshops and Mapathons, which bring GIS professionals together to work and learn side by side with local and refugee community members.

Mapathon: MSF Water & Sanitation Expert mapping in collaboration with community members

The first ongoing feedback event was held on 28th November, for which data collection was suspended, for surveyors to attend. This was conducted, too, in the field, and involved the usual challenges and rewards of field-based mapathons. It demonstrated the field-based inclusive ethos of HOT, and the presence of surveyors and their data clearly cultivated the sharing and integration of data and knowledge between agency and field, and the understanding of the collaborative and field-derived data ethos as a whole. (37 people participated)

Omugo Sub-County Field-Mapping Training – Unusual collaborations between participating agencies

Omugo Sub-County Field-Mapping Training – Unusual collaborations between participating agencies

Strategies of data collection continued to evolve, as the twelve data collectors moved around the district in-between this and the next ‘Mapathon Training’, which was hosted at the UNHCR regional office. This is a field feedback session, where surveyors share thoughts on relevance of survey questions, based on field experience and community feedback. They are later taught how to modify and write such Open Source surveys for themselves.

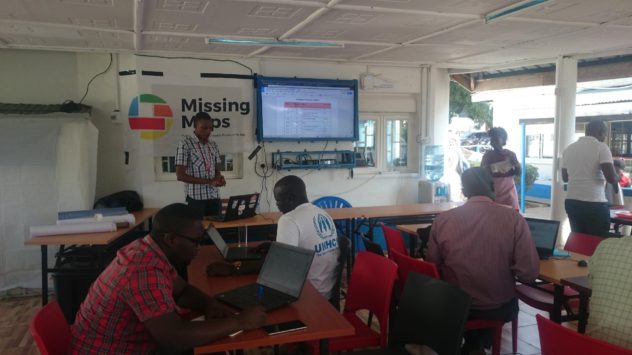

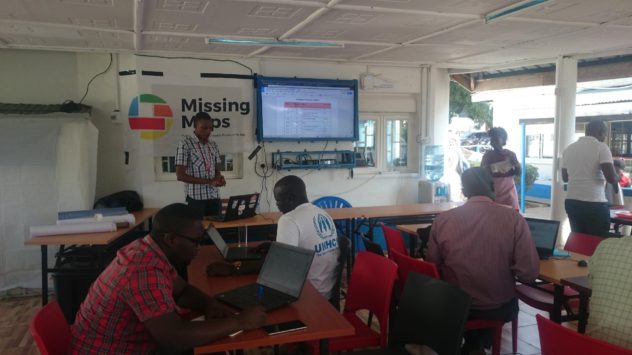

6th December 2017 Mapathon Training, UNHCR Regional Office.

This was a standard OSM training day, tailored for some requests for certain preferred topics and tools. The schedule included Tasking Manager, ODK, KOBO, JOSM, QGIS and Form-Building. All members of the training completed the process of composing a map by the end of the day. Appendix 3 Day Schedule.

UNHCR Training, Arua

All Participants Compose QGIS Map Products of their home environments.

Left to Right: Host Community Member, Refugee, Local Board LC3 Officer, MSF WatSan Officer.

Refugees, Local Community members, and Partners learned tools together in the classroom environment. It was a very rewarding day, fertilised by the field data and mapping experience of the Surveyors, and the cross-referencing of GIS and Data skills which was gathered in the training.

Field Mapping Strategy and Methodology

Mapping strategy is a very important part of the surveying process, as productivity will be halved immediately if progress is not made through an area in a constructive way. A detailed and commonly-understood plan is needed to avoid duplication and repeat surveying, for which local roads need to be known.

A freshly-trained Field Mapper strategising with field-derived community feedback

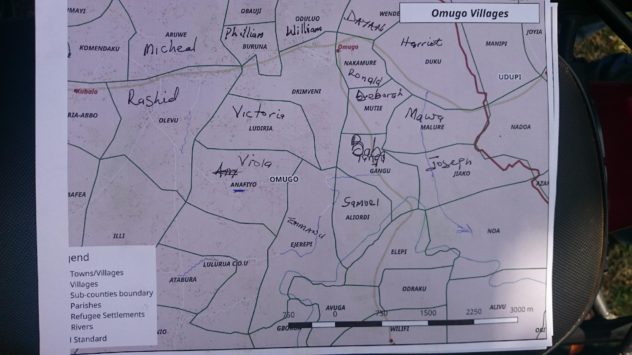

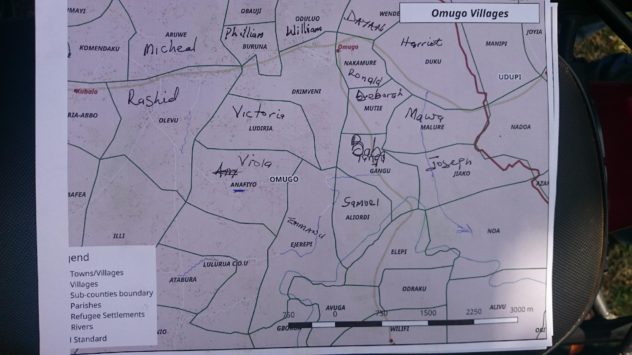

During the planning phase, we were able to access shapefiles of counties, subcounties, parishes and villages from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). This was data which later led to challenges, but was useful to overlay on maps showing settlement shapes (from the UNHCR), and which we used to strategically plan surveyors’ workplans.

Daily Area Coverage – Boundary Shapes Courtesy of Partners: Uganda Bureau of Statistics

The overall map of the area for strategy helped, too, to plan a longer-term strategy. These working maps are consistently printed and used in the field by surveyors. Dark areas denote refugee settlements. Below is an example:

(Map: HOT Uganda. Not for publication)

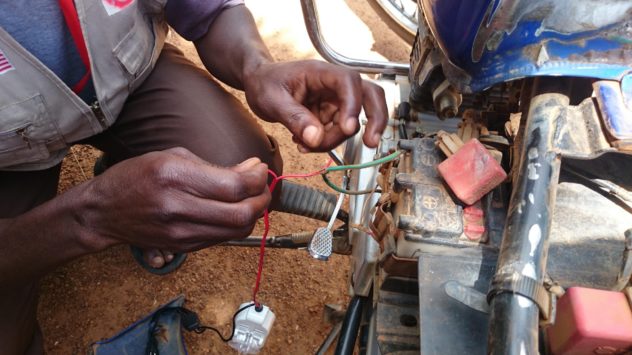

Motorcycle Mapping

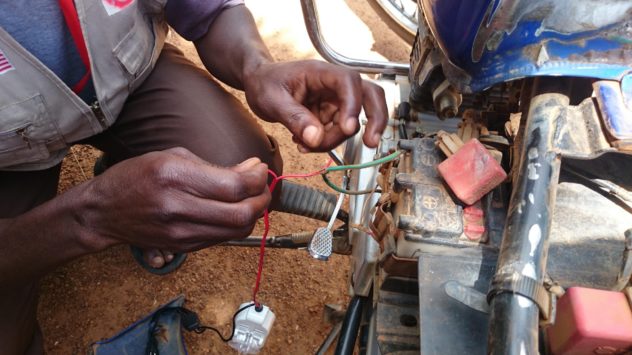

Collaboration takes place through occupational engagement between all participants, and the Motorcycle Riders themselves are encouraged to learn and participate in the process, providing a number of fundamental assets to the table.

Local Boda Knowledge – Riders are involved as team members

‘Hacking’ Motorcycles with Phone Chargers

Training Outcomes

In order to provide the most accurate mapping data which can be accessed both by agencies across sectors and a growing OSM user community, our field mapping content, ground-truthed by the community members themselves, has been interwoven with training in OSM data manipulation and GIS tooling during this time. Mappers from the community have now experienced all aspects of taking data from the ground to the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap, and partners have acknowledged the value and power of the OSM tools and methodolgy.

Locally, refugees habitually now work alongside host-community members in the field (local community surveyors, and local community motorcycle riders), who guide them and translate in non-settlement situations. These Ugandan Nationals themselves learn and interact when navigating/mapping the inside of the settlements.

Michael Yani, Refugee Field Mapper, learning GIS in the UNHCR Compound, Arua

Newly-Established Arua OSM Community.

Since commencement of this phase of ‘Uganda Community Mapping’, we have trained over 75 people in Missing Maps/HOT Field Mapping Techniques, OSM field tools, and desktop GIS and Data-Processing skills.

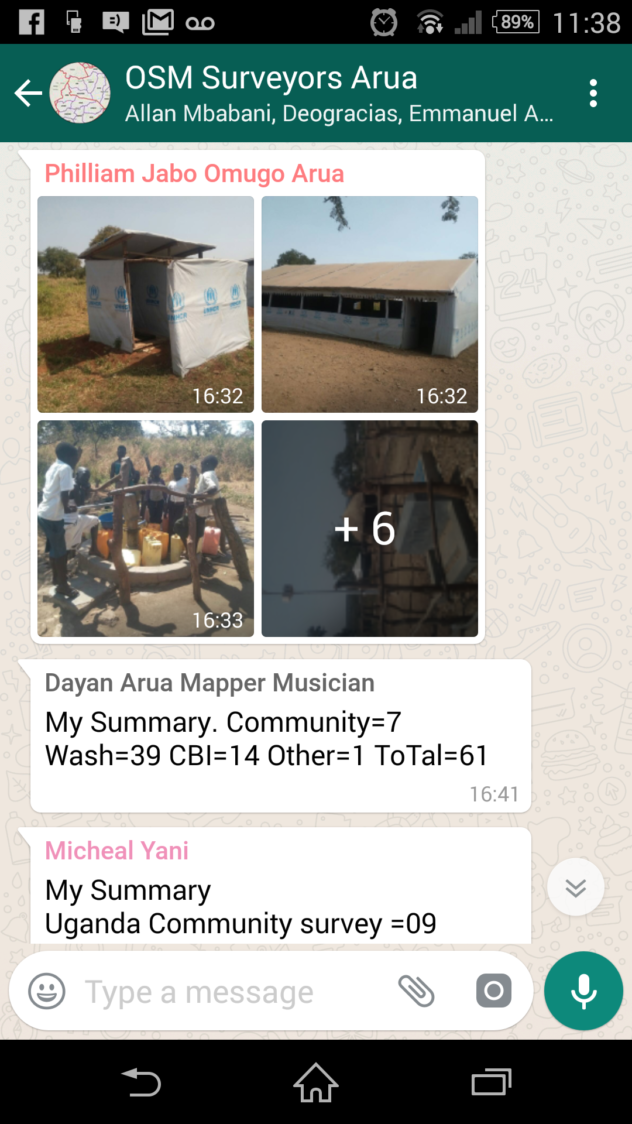

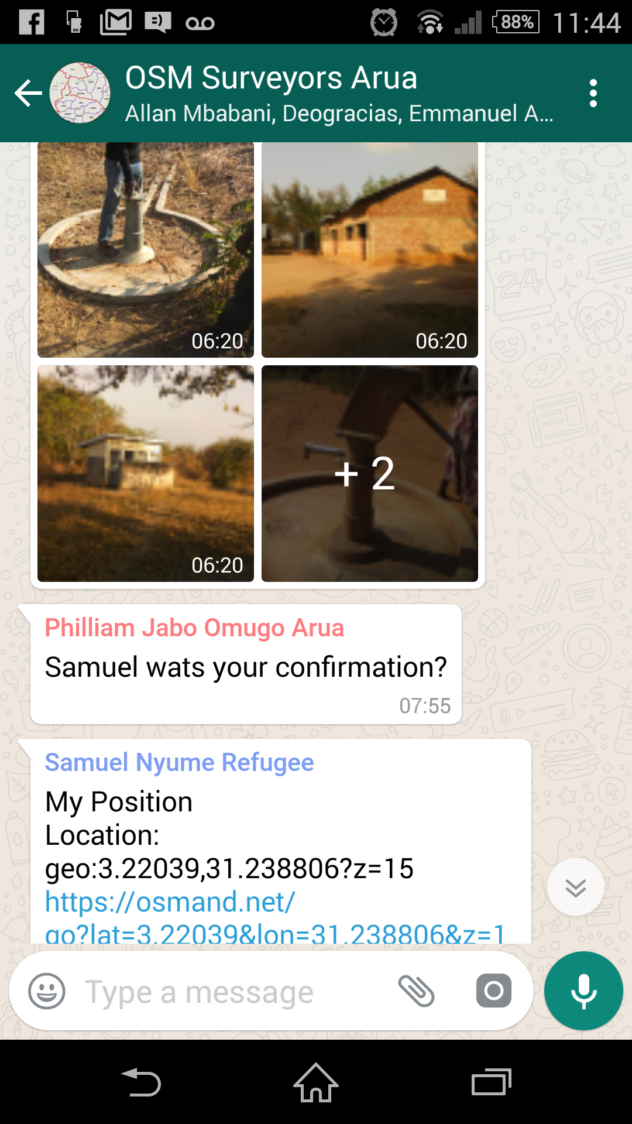

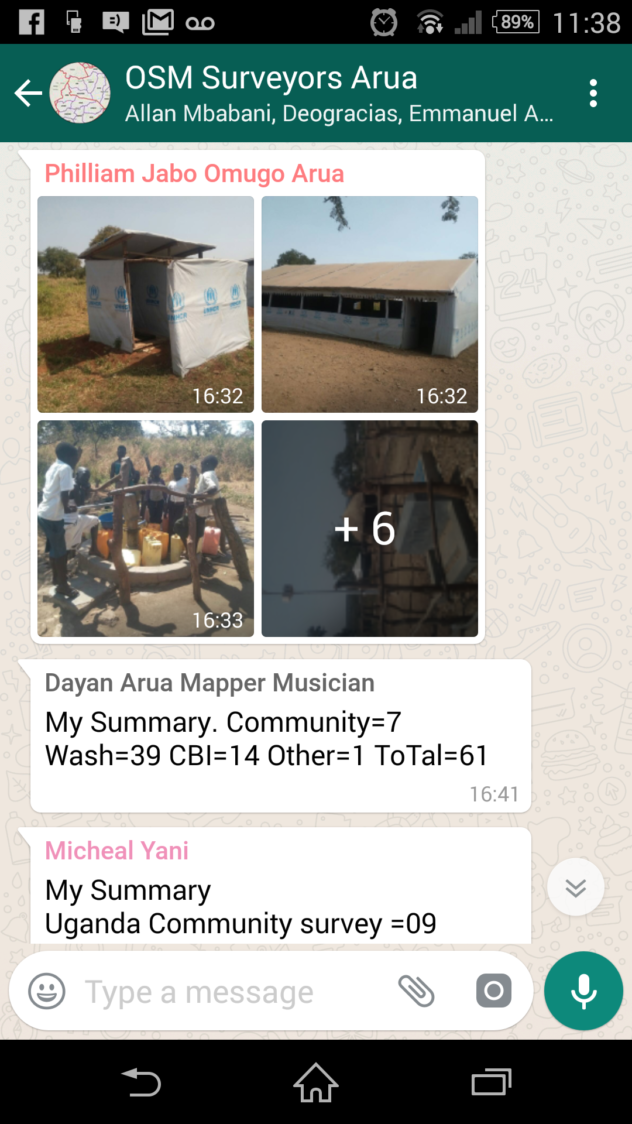

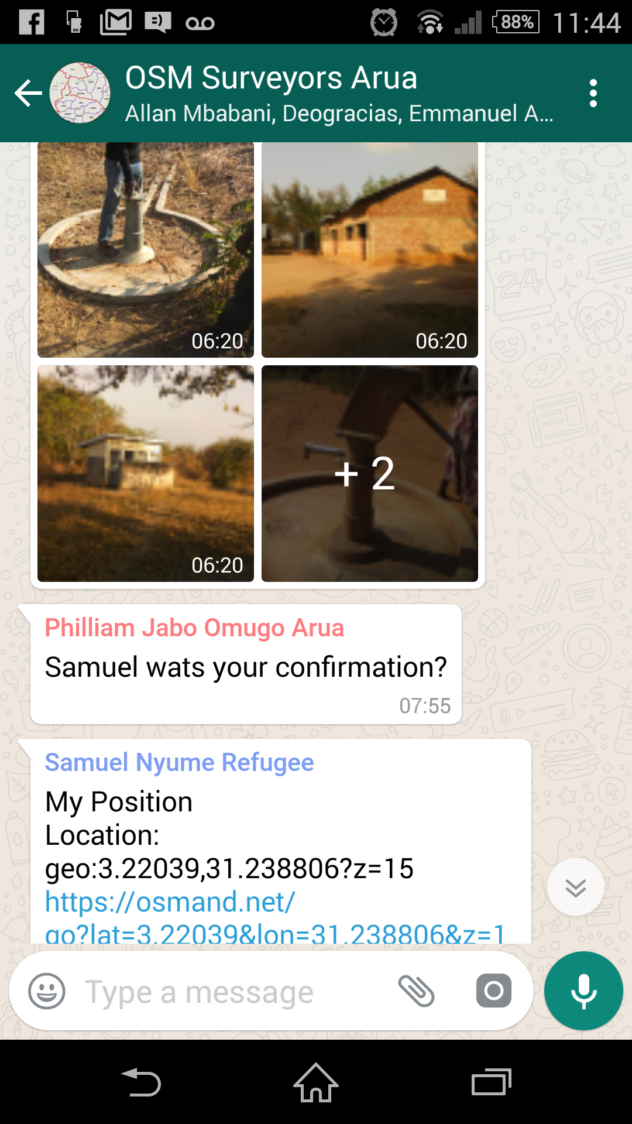

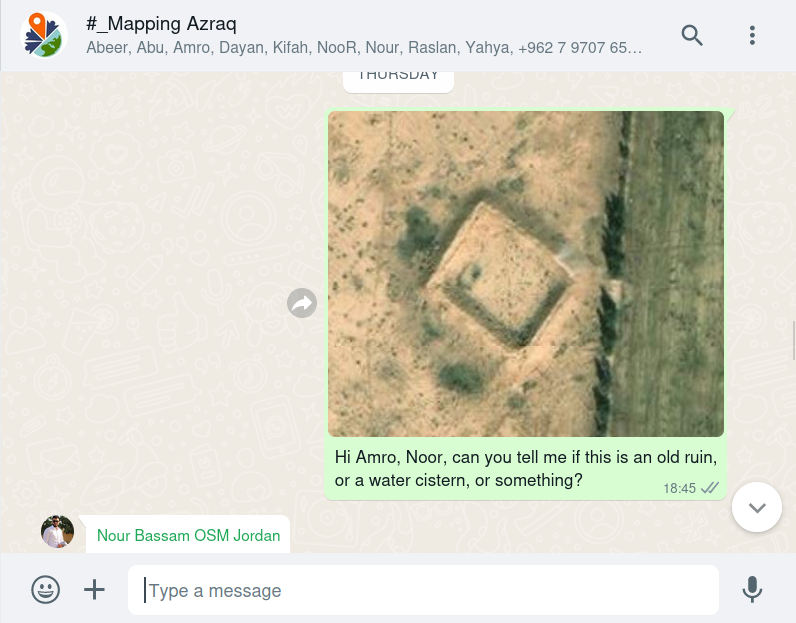

These people constitute the newly-founded Arua District OSM Community, which has a WhatsApp group by which to communicate, and which is used as a resource for ongoing events. 16 of these members were selected for field-mapping in the district, and consist of six Refugee Community members, five Local Hosting-Community Members (Ugandan Nationals), and five independent partner members (from MSF/France and CARE International). This group also communicates and coordinates by WhatsApp, and can be remotely and internationally supervised and connected on this platform.

Mappers share daily progress via WhatsApp

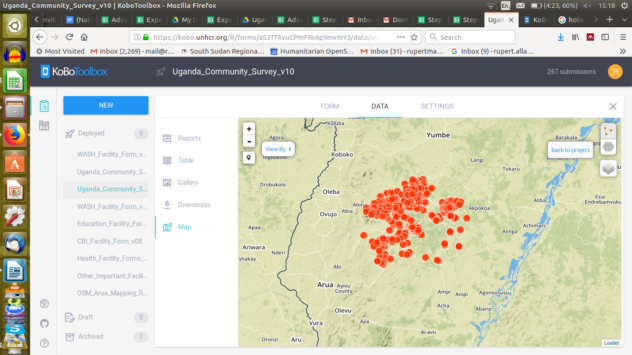

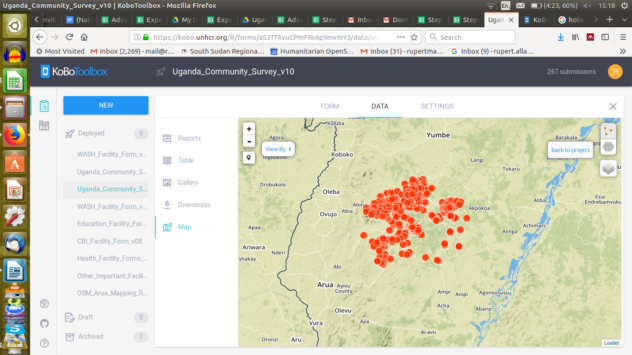

We have also involved UNHCR partners to help coordinate and for community entry. The careful choice of ODK enabled the generation of much interest in the project, due to the power and accessibility of ODK, and its adaptability as an access-point into OSM culture as a whole. Partners without OSM knowledge could easily see the mechanism of Community Mapping as it evolved, producing a working map which could be imagined and understood as surveys appeared on the server and then were used to make focussed map products:

Surveys arriving directly from Field to Server, ready for analysis, cleaning, and OSM uploading (24 hour process)

Embedded Trainings

Around the workshops and trainings, many inter-agency relationships were built, which can potentially serve to reinforce the developing OSM culture in Uganda at national level.

As a result of these practical sessions and field applications, provisional agreements now exist for further partnerships and collaborations with many interested parties. One meeting at UNHCR resulted in the adoption of ODK for field surveying in an immediate project. This demonstrated the potential value of providing partner agencies with embedded training sessions, under the condition that they adopt OSM as everyday practice, serving, and integrated with, the collection of their data. It is hoped that these trainings will remain firmly attached to the community-led way in which the mapping data is collected, and the culture of enterprise embodied in the intrepid commitment of the data collectors themselves.

Training and Orientation: New OSM Arua Members finding their homes on the evolving map

Refugee Surveyor Moses Mawa making full use of the HOT Uganda Mission Order

Additionally, steps have been in the sharing of previously inaccessible data, in contribution to, and benefitting from, the HOT project in Uganda. MSF, REACH and UNHCR are now each running surveys which use our tools and surveys/data models, and trainings and collaborations have been specifically requested by World Vision, IAS, IRC, CORD, World Vision, URCS, and LWF.

Outcome: Partner Access.

Challenges of partner access are tackled firstly by merging proven HOT methods and OSM techniques with locally-found ‘lowest common denominator’ technologies which are already in use (hence the prevalent use of ODK, already a universally NGO-accepted intervention/survey tool). Contributing partners were reassured of the fact that the OpenStreetMap only makes simple geographic data points public, that demographic, political and sensitive data is separated, but that this can be used in an aggregated way to make some powerful analysis. Confidential, sensitive, or inappropriate data is separated, protected, and anonymised at source.

The Evolution of a Community Map is a Stepping-Stone to further advocacy between agencies and within LC and RC communities, upon which to build the next phase of the project – Expansion into Arua, Yumbe, Moyo and beyond.

Monitoring of Most Appropriate Tooling

OSM tools in use are expected to change, and it is important to keep the methodology under constant review. There are many lo-tech and hi-tech OSM tools which ‘hack together’ for crisis-mapping in each context around the world. For tooling use monitoring, a monthly table is updated, with review points to note for accommodating the appropriate suggestion of other OSM tools (e.g. OMK, Maps.Me, OSM Tracker, UAVs, On-Foot Surveys)

Mapping Outcomes/Products

Congestion at Water Tanks – The Majority of Geo-Spatial Data are WASH Interventions also used as an Address/Location System

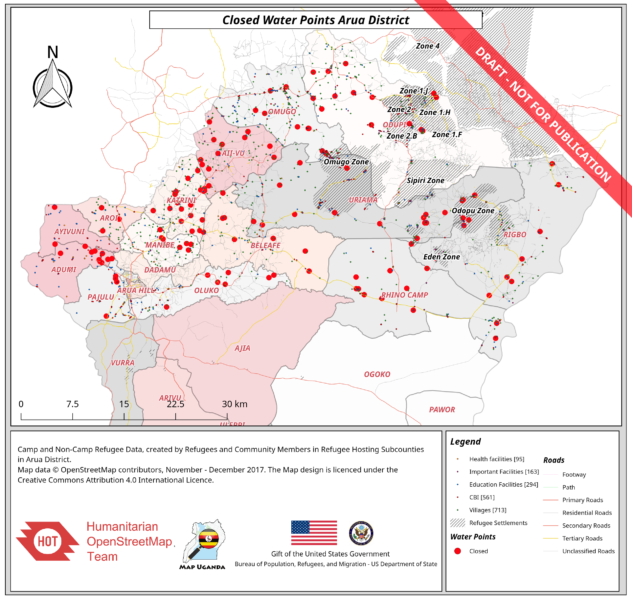

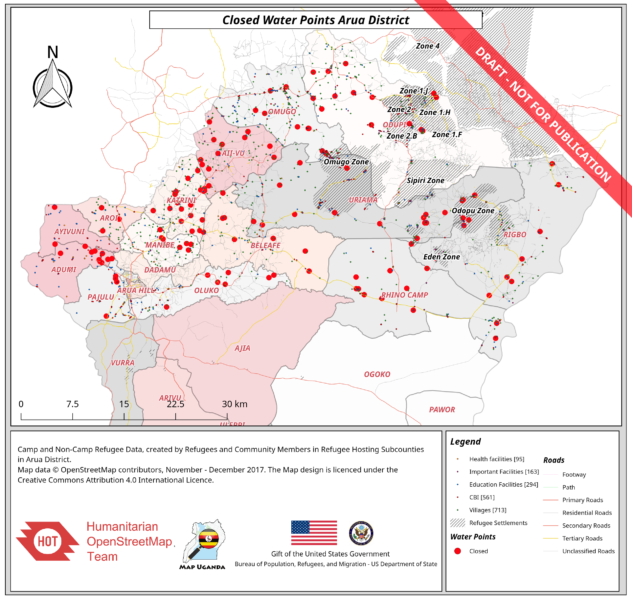

The most important function of a ‘static’ map product which is not the dynamic OSM online map is for use in community centres to gather feedback and detail from interactive community use. It is hoped that map products such as the following draft – a rendering of training data gathered in the first phase of mapping – will be printed-out and displayed, to create a reciprocal understanding that community members can change how their surroundings are viewed and understood by becoming involved in community mapping. The process also serves as a live example of how OSM globally connects communities through commonly understood spatial language.

Click for Interactive Map: Data gathered at 20th January

12th January, 2018 Full-Data Map, visualising ‘All non-functioning Water Points in Arua Hosting Subcounties’.

In the two and a half weeks since field and classroom training started, well-over the recorded numbers have joined the OpenStreetMap community, many have been trained, and many have agreed to provisional collaborations, some of whom have already adopted OSM into their data collection work, and are now gathering OSM data according to our agreed model. The statistics speak for themselves, but are only supported by the continued field-reality of communities getting mapped, and indicators of needs in service-provision being logged. The sustainability of the community and this project itself depends upon these transparent lines of direct beneficiary-to-donor communication being maintained through continued mapping, embedded and public training follow-ups, and ultimately effective and economic intervention being evidenced as a result of the new geo-spatial coverages achieved.

Conclusion

This method of data collection amongst communities in the field integrates important local content with the trainings. It provides both content and incentive at a local level to learn and apply OpenStreetMap through practical mapping of needs and personal skills education. The partnerships derived from these collaborations are multi-lateral, with members of the Refugee Community working alongside NGO partners in trainings, and reciprocating knowledge and skills between the data management process and the field.

Omugo Sub-County Field-Mapping Training – Unusual collaborations between participating agencies

Omugo Sub-County Field-Mapping Training – Unusual collaborations between participating agencies