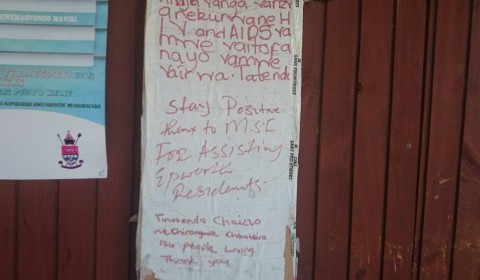

I’ve got a headache. It’s 3pm in a darkened room in Harare. The sun is beating down. A cool breeze blows outside the windows, but the curtains are closed. Children are playing in the street, but we are inside, staring at computer screens. Tomorrow, we will try to describe Missing Maps, and in fact the whole Open Street Map concept to a group of health workers in Zimbabwe. It will become readily apparent that we are there to learn, rather than teach. But we do not know that. Yet.

I have had the great idea that we should print out a huge map of Harare, so that we can explain how we will take squares from it, one-by-one and annotate them, ready to upload the updated humanitarian information back up to the internet. As an MSFer, a career Field-Worker, and Visual specialist, I am fascinated to be part of the Missing maps project. But I have a lot to learn.

-

-

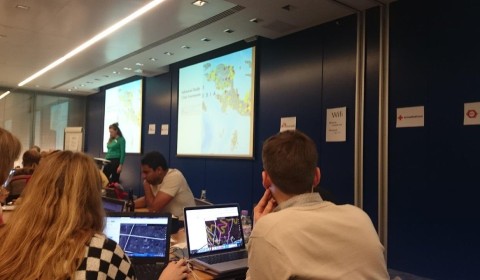

Arup, a posh Civils Company, hosting the Missing Maps Mapathon.

-

-

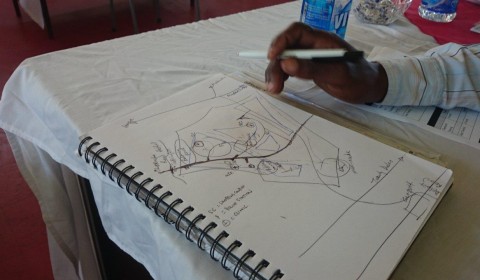

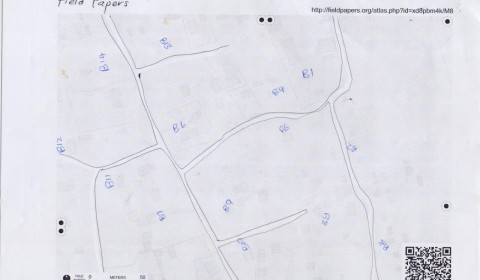

Detail is put in later, the important thing is shapes

-

-

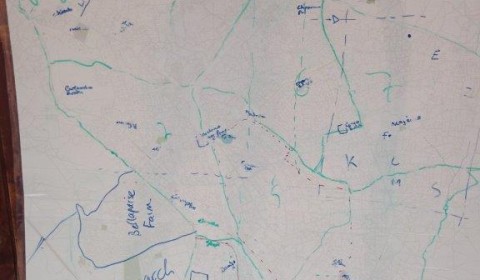

Actual features are worked on across cultures

-

-

I have walked this road

To an idiot like me, printing-off a page from the internet, even if it has very fine detail and needs to be high-resolution, seems obvious. But it isn’t. After weeks of work by international volunteer mappers all over the world, a schematic ‘basemap’ – looking like digital tracing paper – can be found online. Having helped finishing it off at a ‘Mapathon’ a week earlier, we can see it now online from Harare. We can zoom in to the shapes of the nameless houses and schools. We can change it with Java Open Street Map free software. But we cannot make a hard copy.

‘Surely, hard copy is fundamental?’ I’m showing my age, and feel like a dinosaur. If I want to know WHY it works, everybody looks at me blankly. I’m used to image manipulation, and consider that an image is of something, and can be rendered by different processes. Transparency and accountability are all very well, but now, things are falling apart around this table, around this course, around us. We should be able to print everything we see on the internet. The explanation comes that this is a map of the world, and in its infinite detail, to print this map is something like trying to print a picture of the universe. Kieran, my GIS expert, seems completely unfazed. He seems to be enjoying it. I have much to learn. ‘But it doesn’t work!’, I agonise. Kieran is looking at me as if to say: ‘Shut Up’. After about twenty minutes doing whizkid stuff, he does: ‘Just don’t worry, Rupert. Leave it to me’. I met Kieran, a Red Cross GIS technician, at the Mapathon and, with the encouragement of the ‘tutors’ who were running the ‘Mapathon’, learned basically how to use a software which is changing the landscape of humanitarian relief forever.

-

-

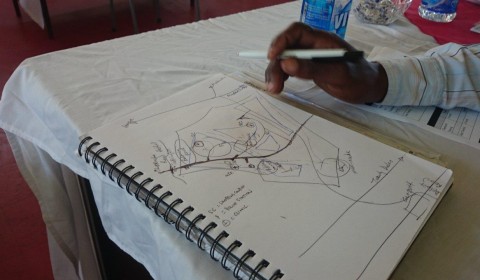

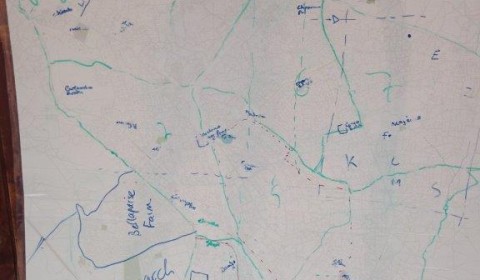

Shepherd’s First Sketches of Epworth

-

-

Learning Together

But now we have very limited WiFi. It is Sunday in Harare, not tuesday in London, and it doesn’t feel like we are changing anything very fast. Both of us have computers which are objecting to the heat. Or something. It has been a gig, last-minute push for me to try to prepare for this work. I am over-complicating things, and I know it. Swamped in new technology, I am a nervous wreck.

‘We really need this map.’ We both say, almost in unison.

Eight o’clock rolls up. We have 12 hours to go. ‘We’ll just put it out there. Somebody’ll build a Jpeg of it.’ says Kieran, finally. We have missed the best of the day, and most of Britain will be turning in shortly. They are about five thousand miles away. But Kieran’s calmness is reassuring. How does he do it, I wonder…

We are ‘remote’. Or are they ‘remote’? Depends what you call reality. We both agree that somebody, amongst the worldwide community that made this very map from aerial images and sheer hard work will like the challenge of creating a document we can print from their map. The software doesn’t do it, because it hasn’t been needed up until now, and it is free and by nature experimental.

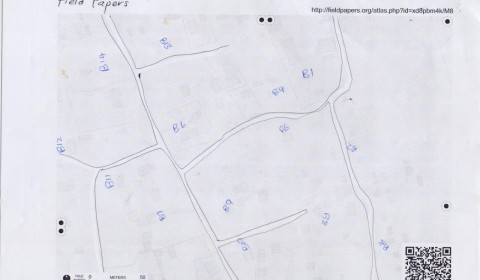

By ten o’clock the next morning, Kieran rocks into our briefing in MSF’s Zimbabwe Headquarters. He is beaming, clutching a memory stick and a huge AO -size ‘blank’ map of Epworth, fresh from the printers we have found, improbably close to the MSF safehouse where we are staying. A massive, finely-detailed AO-sized poster of our entire suburb. A map of Harare, manifested in the flesh for the first time, made by volunteers from their own homes all over the world. Made into a Jpeg image by a bored GIS whiz on another continent in the small hours. Printed out on a back-street of Harare. This is a true ‘Co-Op’. The Open Street Map community. It all exists in windows and layers, it seems. Across cultures. In London, we are dealing with a layer of data on top of a satellite photo of the area. We are making a trace. A load of London City-dwelling volunteer humanitarians with an interest in computers and skills in GIS. The geek shall indeed inherit the earth. We are ready to map…

-

-

We finally have our basemap!

-

-

Figuring out what’s where on our remotely traced layer

-

-

Inputting in the Field

-

-

Learning Together

-

-

Drawing-in the Neighbourhood Boundaries

-

-

Superstar Teckla, the Shona Mega-Mapper

-

-

OSM Registration

Then it is five days later, and I am walking through the neighbourhood of Glenwood, Ward 6, down a footpath, with farms across veg plots on each side. Chipo, Esther, Landiwe and I hear quite a noise up ahead through the grasslands. It is idyllic, and hard to think of the place as the precarious ‘slum’ described in the briefing. But the grassiness and tranquility belies the fact that there is no water here a lot of the year and, perhaps more importantly, no sanitation. Not a single drain.

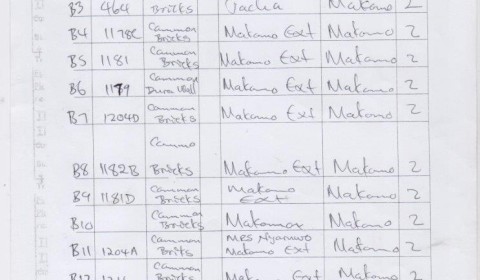

Indexing this map through the eyes of the mapper on the ground, we round a large tree with our printed-out section. The source of the ruckus becomes self-explanatory. It is a small farmyard, woodsmoke spilling out, decorations on the whitewashed walls, and not a soul to be seen. Motorbikes clog the entrance, and we look from outside at the way the place is held together. But the Zim DanceHall is blaring out. I struggle not to move as music pushes through the fug of woodsmoke. Somebody is having a party. We stop to input the data onto our Map Form. Name of house. Use: Residential. I hear the music and think of nightspots in carefree London. Then I think of the mapper in that West-End office that night who traced this particular building in readiness for us to be standing here, the ‘colleague in the field’, inputting data.

-

-

-

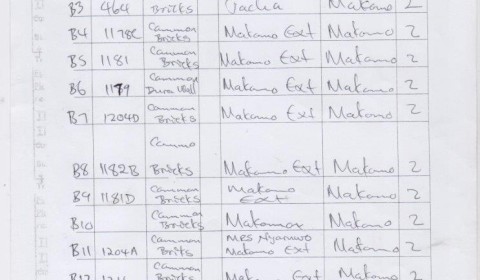

Somewhere Between B5 and B6 is the house. You can look it up now!

-

-

-

It was NOT this house!

As I walk along I am swaying to the music, and we are all laughing about my rhythm. We put the house on the field paper. But I wish I could go in, and as we move onto the next data entry on the form, and I squint at the GPS arrow on my Android Screen, I am reminded of Robert Frost’s ‘The Woods are lovely, dark and deep, but I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep’. I linger, but the others are already noting down the next settlement on our massive list. We have mapping work to do. I am starting to think differently. About layers, about maps, about addresses. I hurry onwards between the boulders in the Savanna grass.