As a child, you see things up-close and remember them. A scratch on a tabletop, a chip in a skirting board. My grandmother was called Molly. She always had a powder tin to hand, to dab the skin-coloured pink powder over the tiny blue blood vessels you could see all over her nose. She wore nylon frocks and pinafores when she was cleaning. I noticed all of these textures and objects too – some of my earliest memories.

And in her youth Grandma was ‘a sort’, she told us, with a glint in her eye. She had grown up mainly in London, had seen the blitz through with two young kids. Her bright pink lipstick, flaky skin, and grimacing as she moved her arthritis and polycythaemia around her granny flat in the old peoples’ complex made us cruel kids want to get out into the gardens as soon as possible. But amidst all that pain, and the losing battle against the march of time, housekeeping chores, the head-on loneliness of bereavement blossomed into a heroic fight for fun in her last two decades.

In her mid-seventies, she became a character about town, happily compromised many of her principles in order to blithely campaign forwards and enjoy retirement. But underneath Grandma’s blundering old-lady appearance were two things. The most obvious was her fluttering social manner. With a nervous well-spoken aspirational demeanour, she was taken-in by feats of technical brilliance and awestruck by people with any inkling of society. She was a product of that strata of mid twentieth-century who were so useful in Churchill’s War Effort; easily impressed, and doggedly loyal to something they sometimes seem nowadays to have had little understanding of. But that blind faith won the war for Britain. And she was quietly brimming with pride over this.

The second more subtle attribute of Grandma was her canniness. And you wouldn’t have thought it would creep up on you, so long after having known her. She said things which were right, but sounded laughable at the time. She would grab your arm plaintively as she made a point. You couldn’t take her seriously, so embedded was her act of naivete.

Her maiden name was Avery, and there was a famous pirate with this name, John Avery, who we are all supposedly related to. And we probably are. But Grandma had had a series of bounders in her ancestry. Her deified mother – the concert pianist – had died when she was four years old. Her father, the Newspaper Foreign Correspondent had done a moonlight flit, leaving Grandma’s only good memory of childhood encoded in her mum’s practice on the black and white ebony and ivory keys of the piano. So obsessed with these objects was she that she was finally banned from tinkling by her adoptive aunt. And her aunt was never forgiven for this. They had no money for lessons, living in a flapper world of Mrs Dalloway characters, and so she became a secretary as everybody did in the 1920s, it seems.

Her bank clerk suitor (Grankie) whisked her away with his motorbike, salary, his wartime fire-watching derring-do, and eventually his farmer grin. He was a campaigner, too. His politics seem complicatedly right-wing neo-liberal to me now, but he did some good stuff. Grankie had escaped the drone-like life of a bank clerk in the city to become a smallholding fruit farmer, with the family in-tow. She had become a farmer’s wife, and they became forever identified as the ‘Darling Buds of May’. She got freckles in the Kent sunshine as she helped out in the orchard, and he replaced her christian name, Florence with Molly. (Mole-ley, geddit?). And that was who she became. Molly Lake. Forever.

But that was all over now, and as she sat in her ‘home’, with unruly and sometimes belligerent teenagers to control, she tried to take an interest. I was always the technical one (whether I liked it or not, and I didn’t) who was ‘like Grankie’, so birthday presents always consisted of tools.

But as I grew older, my understanding of tools became more serious. It was difficult to be the only boy, actually. There was expectation. It was also assumed that I would be more emotionally robust than my sisters, and wouldn’t mind playing second fiddle (almost literally) to an older sister in her musical endeavours.

So Grandma took to reading The Times. Principles be damned. Or maybe she had always taken it. Anyway, she always fell for the rubbish advertised in the back pages. China ornaments, meaningless medals, ‘collectibles’. And one year she gave me an extra christmas present: ‘I thought it was marvellous,’ she gushed, ‘and such good value for money. It’s meant to be one of the best brands…’. Hmmm.

I opened the heavy little package, the size of a harmonica case, and my heart sank. A ratchet screwdriver. Bright yellow plastic. A clicking mechanism. Small phillips and flat-head bits to go in the hexagonal holder. Plastic. Yellow. Great. ‘Thanks Grandma’.

Like so many things you hate, it went in the bottom of the toolbox. And like those things, it kept working long after I wanted it to. But to my extreme consternation, I unexpectedly started to see its uses.

When I first went on a film set as an on-set Art Director (Standby), it was always in my pocket or bag. And the ratchet never broke. People would ask me about it, and we would notice that it was made in the USA, and that you could throw it on the floor and it wouldn’t break. Time passed, and at some point, when I was supervising a trainee, I explained it to her, and we christened it ‘Molly’.

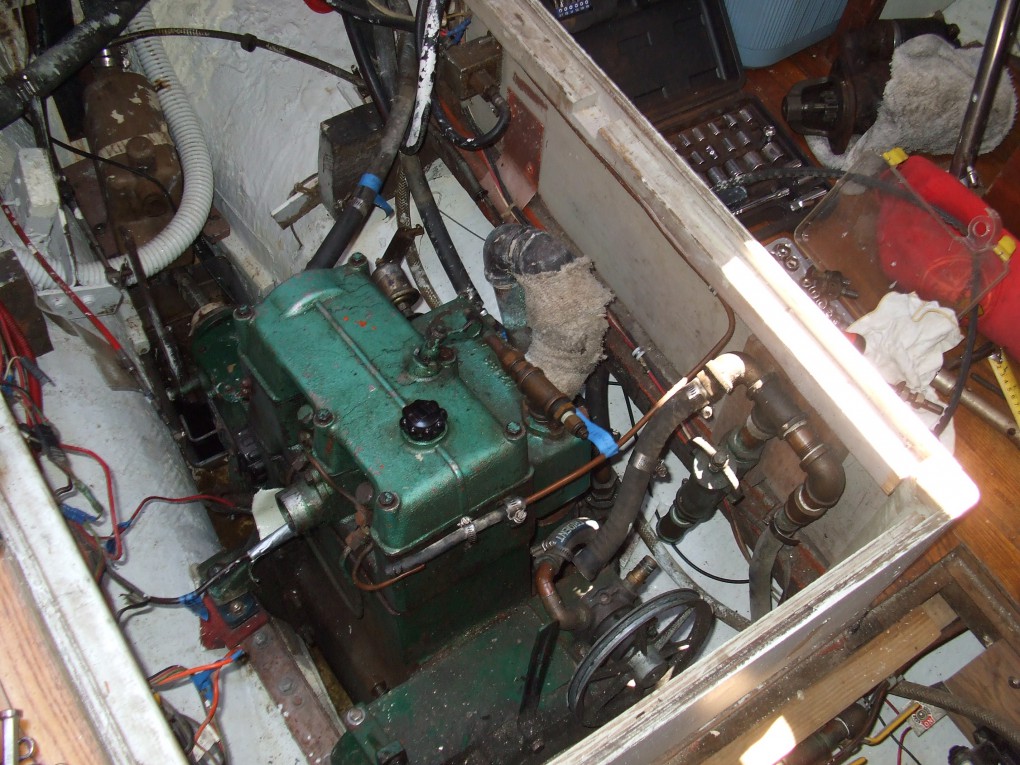

And so Molly became part of my lifetime kit. And like so many other things I have hated, I came to love it, and thirty-four years after getting her for Christmas, fifteen years after Molly Lake’s passing, ‘Molly’ is still getting me out of trouble mid-ocean, in storms. So once again, as I tighten-up another inaccessible screw-bolt, stopping the boat from filling with water, I look back at that improbably wisdom of my ridiculous grandmother and silently thank her in the darkness. I get up out of the heaving hull, my own knees creaking now, and stagger back onto the wave-washed decks of my boat where my crew are trying to grasp the bucking wheel: ‘All done; fixed! I’ll take the wheel. What’s the course?’

Thanks, Molly.

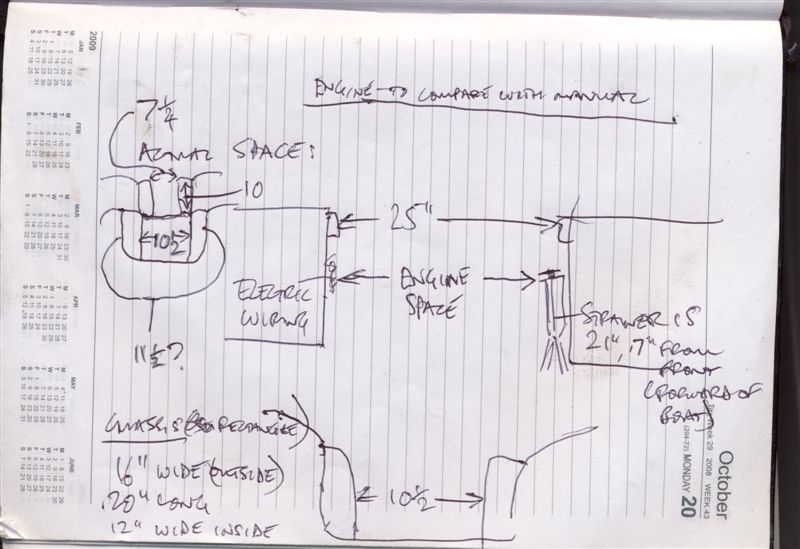

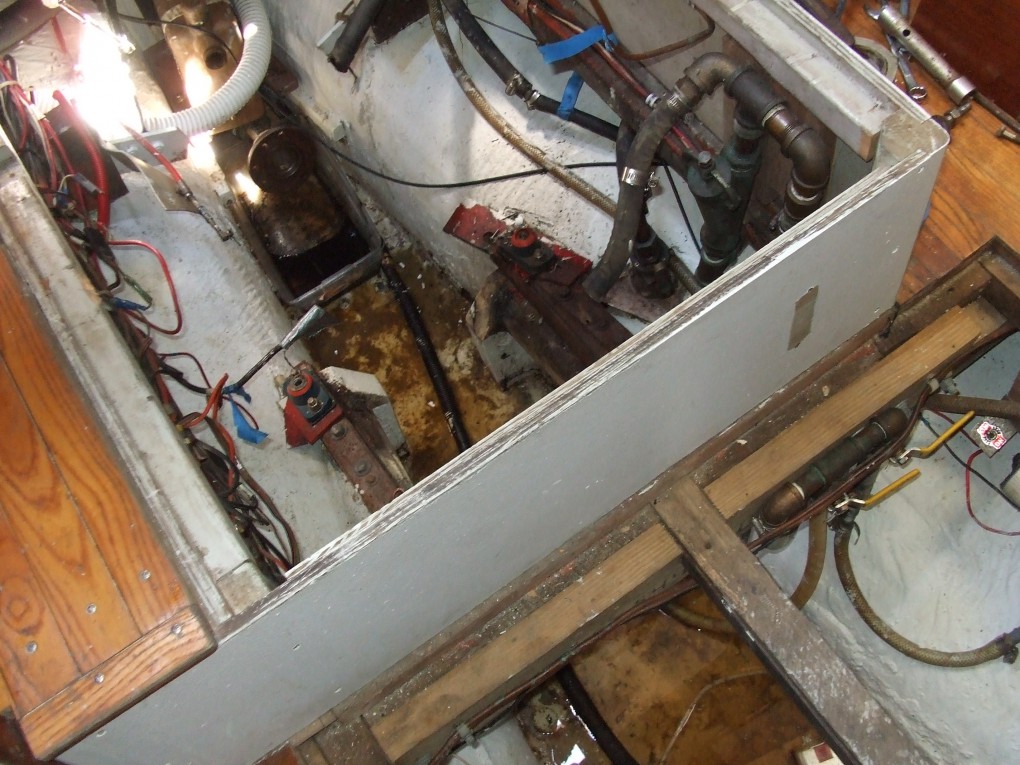

Molly, fixing the fresh water pump on Sandpiper’s plumbing system