Mapio Lleisiau’r Tir / Mapping Land Voices – August 2021

Stories of the forest sound archives: https://www.peoplescollection.wales/collections/1102166

Who knew that there were crofts hidden in the hills of my next-door village in Wales? I didn’t until very recently, when we started listening to the British Library/National Library of Wales sound archives collection.

Dai Morgan, the Horse-Boy

I mean sure, Dai Morgan used to lean on the garden fence between our houses and tell me stories about running away with the mountain ponies when he was a young horse-boy. So near-by and yet, in another village. Dai used to point over towards the north side of the Ystwyth Valley and, conspiratorially, quietly say, ‘they’re different, those people. North Wales, you see. They think differently’. Less than a mile away.

Dai also told me a story once, about when he had been a Gwas (households had several of these ‘farm servants’) as a lad. He was a horse-boy, and was fascinated with the personalities and breeds of the mountain ponies, which, he said, were four types, which never interbred. He was convinced of this, saying that the original Cardiganshire ponies were russet, yellow and grey, all with white flashes on head and hoof. One day, he was in a far field of the farm in Bont, when the wild horses came down to the fenceline. Dai managed to coax one close and jump on. It bolted and he clung to its bare back, as the whole group of them ran back into the mountains. On and on they ran throught the night, until they came to a small upland stand of trees by a deserted stream and suddenly stopped.

‘It was their home’, Dai explained. ‘I was able to jump off, but it took me hours to walk back, through the night, and I just arrived in time to dodge trouble and do the milking at 5am.’

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

I can see it now in these crofts. They had a local perspective. And even though hill-people were mobile – many even lived away for a few years and worked in London – that was most certainly a foreign migration, reminding me of the London Kurds or Portuguese.

When they were back on their lands, it was exotic, too, for Nant Stallwen to marry into ‘Llew Goch’ (meaning: the family running the pub in Bont). It was 10 miles away, if that. Such households were known as communities in their own right, and would turn up to events as an geographical entity – Nantrwch (stream of the sow), Maesglas (blue field).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

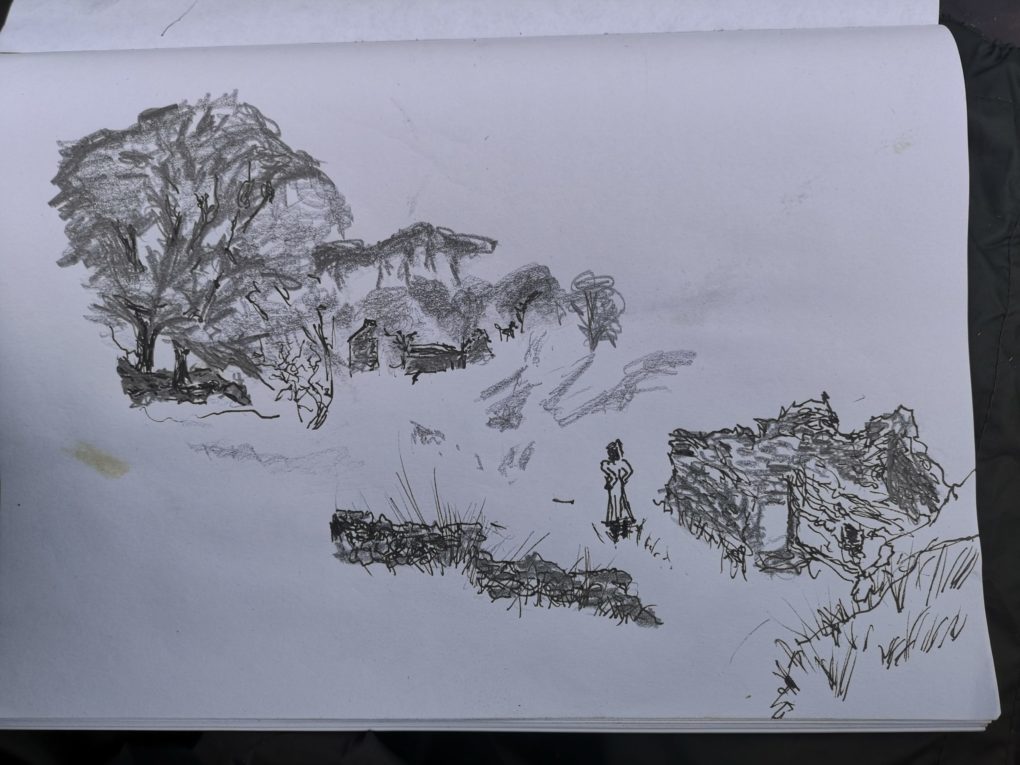

We’re listening to these interviews whilst we sit and draw. Mountain voices. Some coughing, laughing, straying from the question. It’s a very wild but intimate feeling as the rain speckles your face and you imagine similar tactile experiences in this space 60 years ago.

When Peggy Maesglas from (Soar y Mynydd) was diagnosed with Hiraeth as a boarding school pupil in Tregaron, her family left the farm-hands running the farm ‘household’ and moved down to town to give her the support she needed. These were close communities, and Peggy also remembers that Nant Stalwen farm would have two or three thousand sheep shearing, and over 100 horses would be gathered, as all the shearers from the hill farms around – men and boys – would muck-in.

When chapel was on, and the preacher visiting for the weekend, again there were horses. Hundreds of them, grazing the near bog. As well as a chapel which was taken to Bala on the back of a lorry,Tom Bronant tells of breaking the ponies in record time by doing on the deep bog, where they would tire much quicker than back in the lowlands.

Tom’s recollections of Caio Evans leading the Free Wales Army on horseback manouevres up on the Devils Staircase and around Llyn Brianne are coupled with tales of all the ‘bois’ grabbing a lorry in the middle of the night in Tregaron, and coming up to sing outside Nant Llwyd, to see off a bride-to be. They turned up some time after midnight, and even the dogs were scared by the noise! The lights at the farm went on, the doors opened, and they were welcomed in to party forester-style into the small hours.

And ‘Nant Llwyd’, as a household, were legendary, with family and gwasau (farm-hands) comprising a formidable force when it came to horsemanship and community events. But it was Peggy Maesglas who features as the ‘man vs horse’ competition champion, and known for the finest horsemanship in the area, she could get back from Tregaron to Soar in less than an hour, if she hurried.

The reputation of Caio, and his character, are easily forgotten these days, As is the very comprehensive threat which the FWA implied for Westminster. Caio’s leadership and physical presence comes across in different accounts, though, and he was clearly universally admired – almost like (and contemporaneous with) Che Guevara. Organised and agile, his well-put-together group seems revered as a not inconsiderable guerilla force. And the hills, unroaded but easily-navigated by skilled horsemanship, must have presented an important dilemma for the antiquated machinery of a threadbare post-war english task force.

These landscapes are boggy and hard to navigate. But roads – even tracks – were less important when you consider that everybody had a horse which could graze the mountain grass. Free fast transport for everybody. And Peggy Maesglas says that the roads that the forestry brought in destroyed the communities. The sound archive research continues next month, with Stories of the Forest from Soar y Mynydd and Nant Doethie.