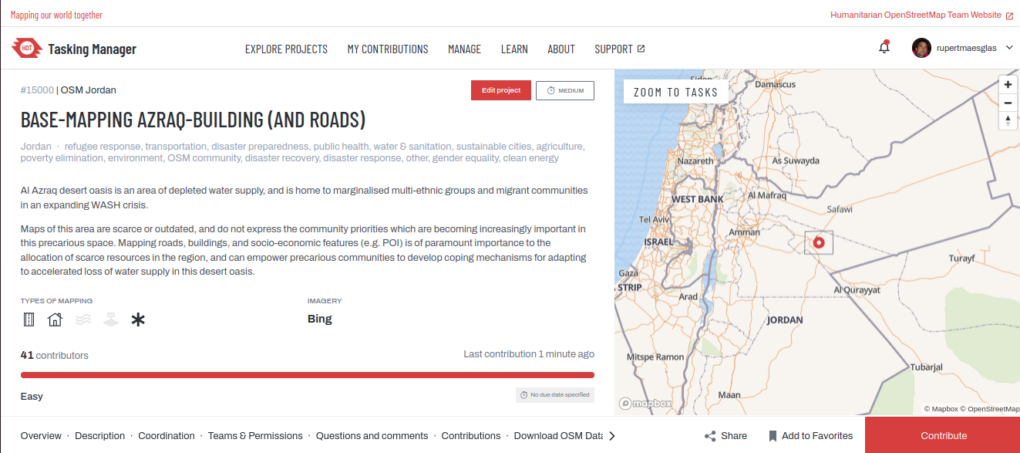

The Jordan ‘Community-Mapping Climate Memory’ project aims to help local people map how they and their livelihoods are adapting to extreme and accelerated climate change. In Al Azraq desert oasis, OpenStreetMap (OSM) is getting used to record cultural practices as a living archive of usable community assets. The project draws on a legacy of OSM projects mapping critical resources, traditional coping practices around these, and the narratives that link them. Our mission is to establish a common frame of reference for multi-ethnic cooperation, to manage diminishing resources in a place where the same landscape has different meanings for different peoples.

Our Community Mapping team is adapting methods used in humanitarian scenarios, where emergency and development resource management has benefited from community input, to connect climate science with hyper-local lived experience. By leveraging OpenSource Community Mapping methods, the community will have an ‘auto-ethnographic’ hand in practical, participatory solutions to climate-affected issues in their immediate locale. We hope that citizen science can record this visibly-unfolding climate crisis, promoting cultural visibility and local economic resilience. Convening Princess Sumaya University (PSUT) YouthMappers, OSM Jordan, and the national Wikimedia foundation as collaborators, we hope it will create a national precedent.

It’s an exciting project, not least because of the location, amongst the desert castles and pathways of the Arabian Peninsula, steeped in history and visually stunning. OpenStreetMap Community Mapping is, by definition, adaptive. It bolts together different elements of OpenSource knowledge and tooling to suit community needs locally. This project is no different. It’s experimental. Much trialing and consultation time has been necessary to create a unique and innovative methodology for the particular needs of this culturally-diverse region. Connecting OpenStreetMap with what I’m calling ‘The Wikisphere’ seems to clearly resonate with these communities.

Why Azraq?

Around the world, hyper-local connections with the land have been slowly occulted over the past few centuries by the rise of industrial agri-practices. In Al Azraq, this has happened within three decades. The loss of age-old livelihoods of fishing, growing, trading and herding has led to economic deprivation, but this sudden and catastrophic change has been accommodated by the communities in creative ways.

Measurable documentation of human resilience in the face of change may provide unprecedented insights for wider sustainable changemaking. Recognising the cultural significance of Al Azraq, these insights, we hope, can be extrapolated as a regional exemplar of how local issues bear on the wider global climate change agenda. Social capital remains strong in community memory here, and the story and heritage still linked to the landscape can give better public understanding of both vulnerability and resilience in these under-represented communities.

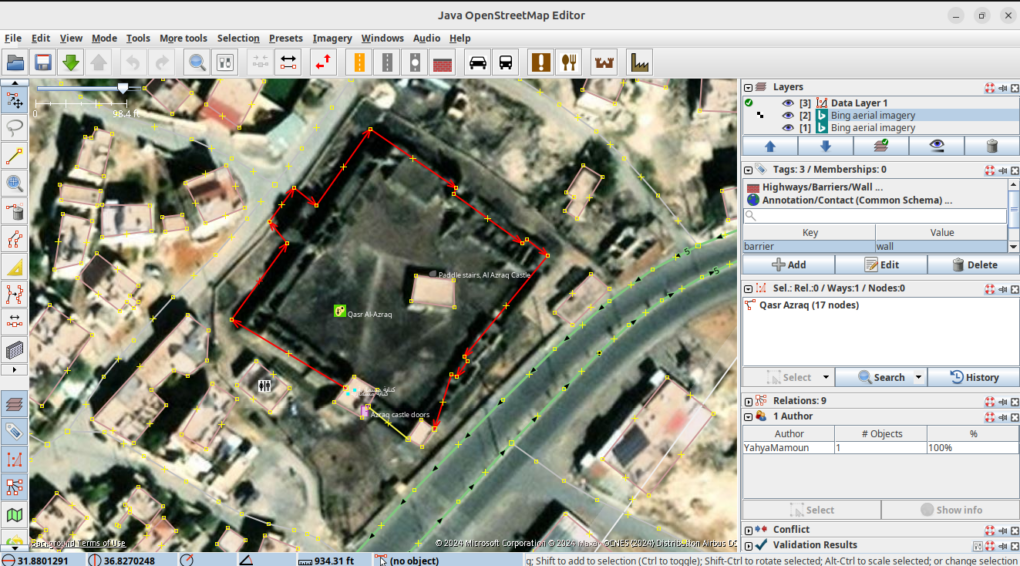

Al Azraq is in the Black Desert, fifty miles East of Amman, in modern-day Jordan. Lawrence of Arabia was Headquartered in this formerly beautiful, verdant oasis. Historically, it holds major national significance for Jordanians. The area is surrounded and embedded with layer upon layer of history and culture. Yet visitors to Al Azraq may be surprised even to find more than some tents around a ruined castle. Google shows one or two hostelries and some commercial entities, some buildings, but as a prime cultural site and destination, Al Azraq seems invisible. One tourism page even reads: ‘The town of Azraq itself is small and does not offer anything of particular interest, apart from the nearby castle’

Azraq’s Castle is famous, but other desert castles also litter the area, even in town, with stories of buried treasure, wild animals, hunting and desert skirmishes infusing every street corner. These stories are the real character of Al Azraq. They are hyper-local folk histories about rituals and technologies which are in danger of being forgotten.

Operations:

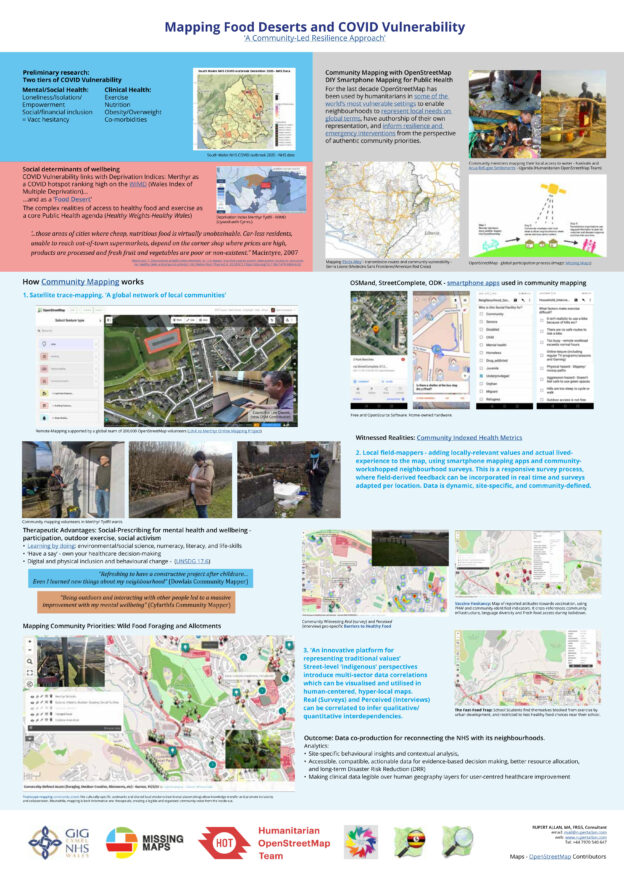

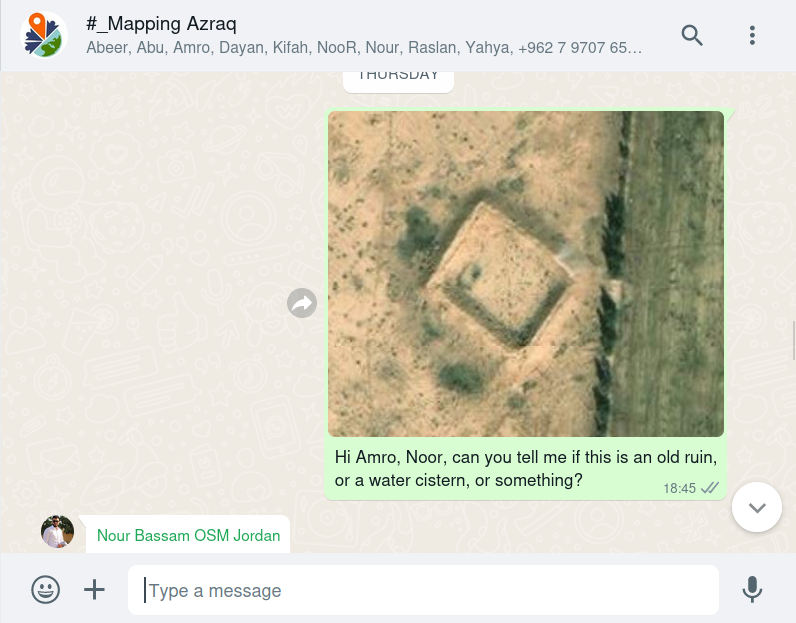

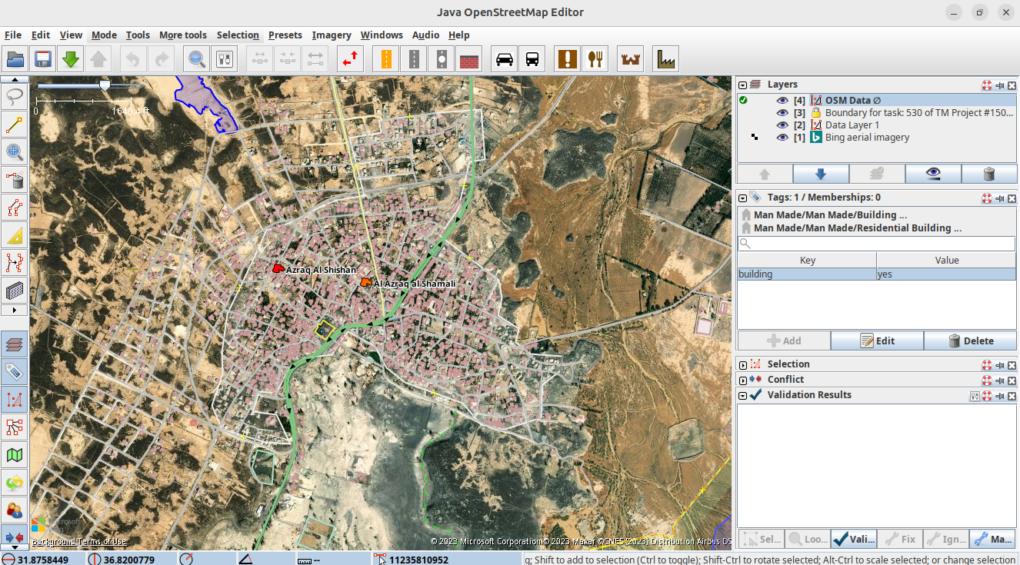

Our project proposes that a visualising something different than western tourism interests could help Azraq survive it’s particular climate crisis. Something that the community can own, edit, and develop for themselves. So for the past months, in an organised editing campaign, we have been creating a ‘basemap’ of the area. From scratch. This is now ready for data to be added from the local community.

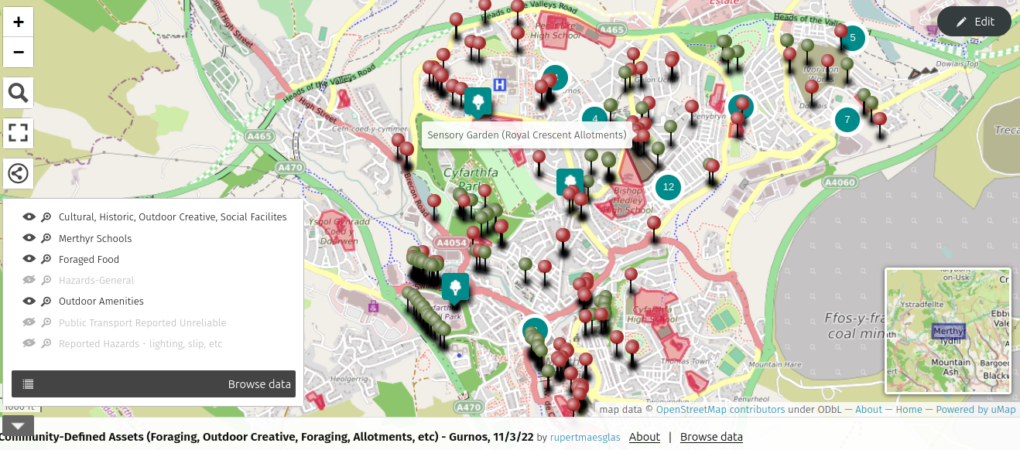

A team of multi-national OpenStreetMap volunteers have been drawing around houses and roads on satellite imagery, to create a ‘base-map’ of every building in Al Azraq, as digital shapes. We created a mapping task for Al Azraq, on the global Tasking Manager platform run by Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. Accompanying the task are instructions, and documentation is maintained and updated on the OpenStreetMap wiki. Edits currently represent contributions from English, Scottish, Welsh, Lugbara, Luganda, Druze, Bedouin, Syrian, Palestinian, and Sheshen origins. I may have missed some!

OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap is particularly good for visualising hyper-local human-based interests by enabling community visibility through measurable ‘home-made’ GIS data. Community Mapping can be used by communities to represent their needs, assets and cultural capital, and thereby to have a say in their own resource allocation.

This is the first time that a whole town has been comprehensively base-mapped in such a way in Jordan, and it represents a progressive regional first, allowing community-led Open Mapping to shape a field-derived research agenda at national level. Jordan enjoys a reputation for multi-ethnic unity, and it is exciting to feel part of this agenda, connecting such diverse local interests with global development themes.

We have now been remote-mapping for some months, and Dayan has been helping from Uganda. It is a truly intercontinental project, and exciting to convene trainings where his refugee-mapping expertise is supporting the team from a small rural house on the South Sudan borders. The brand new community map now appears in phone Apps like Maps.Me, AllTrails, AppleMaps, TomTom, anything using OpenStreetMap.

And on the ground, we are starting to gather a collective of “Practical Community Mappers” across local communities to record land-based skills, history, and lived experience. Place-based practical knowledge is still embedded within living memory in Al Azraq. It is an intangible heritage we can still access, representing remnants of a self-contained local economy. People still remember how this worked.

The aim of this project is to leverage a rich history of rural resilience, agility and inventiveness; to help Azraq’s people express socio-economic and cultural visibility, but also to create actionable methods for future generations to have a pro-active voice. To help create this science communication capacity, we have the privilege of Prof. Iain Stewart’s expertise leading the project. As broadcaster, science communicator and geologist, Iain has centralised community-owned data in his research agenda as UNESCO Chair at the Royal Jordanian Scientific Society (RSS).

Watch this space for updates on our progress.